Paper Math: rsLoRA

Background

In this notebook, I’ll work through Definition 3.1 and the Theorem 3.2 proof provided in Appendix A of the rsLoRA paper. Note that the purpose of this blog post is to help me think out loud—I have a lot of gaps in my understanding of matrix calculus that I need to remediate before I can derive some of the core equations in the paper. This post doesn’t provide those derivations.

Definition 3.1

An adapter \(\gamma_rBA\) is rank-stabilized if the following two conditions hold:

If the inputs to the adapter are iid such that the \(m\)’th moment is \(\Theta_r(1)\) in each entry, then the \(m\)’th moment of the outputs of the adapter is also \(\Theta_r(1)\) in each entry.

If the gradient of the loss with respect to the adapter outputs are \(\Theta_r(1)\) in each entry, then the loss gradients into the input of the adapter are also \(\Theta_r(1)\) in each entry.

I’ll define the following keywords from those two conditions:

- iid: independently and identically distributed

- \(\Theta_r(1)\): Big Theta notation, which specifies the upper and lower bounds of complexity of an algorithm. A notation of \(\Theta(1)\) means the function or algorithm is upper bound and lower bound by a constant, meaning that as the number of inputs increases, the function stays constant (represented by the \(1\)).

- moments: quantitative measures related to the shape of the function’s graph (1st moment of a function is its mean, 2nd moment is variance, 3rd moment is skewness, 4th moment is Kurtosis).

Condition 1 says that rank-stable adapters are those where IF the inputs to it are iid and have, on average, constant moments (like mean and variance) as the number of inputs increase, then the outputs of the adapter have constant moments on average as well.

Condition 2 says that the gradients of the inputs and outputs of rank-stable adapters, with respect to the loss, are of constant size as the number of inputs and outputs increase.

This HuggingFace community article puts it nicely and succinctly (emphasis mine):

In the work Rank-Stabilized LoRA (rsLoRA), it is proven theoretically, by examining the learning trajectory of the adapters in the limit of large rank \(r\), that that to not explode or diminish the magnitude of the activations and gradients through each adapter one must set \(\gamma_r \in \Theta(\frac{1}{\sqrt{r}})\)

This Khan Academy gives a nice example of \(\Theta(n)\) from which you can imagine what \(\Theta(1)\) would look like (instead of upper bound being \(k_2 \cdot n\) it would be \(k_2 \cdot 1\); instead of a lower bound of \(k_1 \cdot n\) it would be \(k_1 \cdot 1\). In other words, two horizontal lines of constant value as \(n\) increases).

Theorem 3.2

I’ll restate Theorem 3.2 here for reference:

Let the LoRA adapters be of the form \(\gamma_rBA\), where \(B \in \mathbb{R}^{d_1 \times r}\), \(A \in \mathbb{R}^{r \times d_2}\) are initialised such that \(B\) is initially \(0_{d_1 \times r}\), entries of \(A\) are iid with mean \(0\) and variance \(\sigma_A\) not depending on \(r\), and \(\gamma_r \in \mathbb{R}\) such that \(\gamma_r \rightarrow 0\) as \(r \rightarrow \infty\).

In expectation over initialization, assuming the inputs to the adapter are iid distributed such that the \(m\)’th moment is \(\Theta_r(1)\) in each entry, we have that the \(m\)’th moment of the outputs of the adapter is \(\Theta_r(1)\) in each entry if and only if:

\[\gamma_r \in \Theta_r(\frac{1}{\sqrt{r}})\]

In expectation over initialization, assuming the loss gradient to the adapter outputs are \(\Theta_r(1)\) in each entry, we have that the loss gradients into the input of the adapter are \(\Theta_r(1)\) in each entry if and only if:

\[\gamma_r \in \Theta_r(\frac{1}{\sqrt{r}})\]

In particular, the above holds at any point in the learning trajectory if the assumptions do, and unless \(\gamma_r \in \Theta_r(\frac{1}{\sqrt{r}})\), there is unstable or collapsing learning for \(r\) large enough.

Gradient of Loss \(\mathcal{L}\) with Respect to Adapters \(A\) and \(B\)

Let \(f(x) = \gamma_rBAx\), and \(\mathcal{L}(f(x))\) denote the loss.

Let \(B_n\),\(A_n\), denote \(B\), \(A\) after the \(n\)’th SGD update on input \(x_n\) with learning rate \(\eta\).

Recall that \(B_0=0_{d \times r}\), and see that for \(v_n = \nabla_{f(x_n)}\mathcal{L}(f(x_n))\):

\[\nabla_{B_n}\mathcal{L} = \gamma_r v_n x_n^T A_n^T\]

\[\nabla_{A_n}\mathcal{L} = \gamma_r B_n^T v_n x_n^T\]

This comes from the chain rule. Since \(\mathcal{L}\) is a function of \(f(x)\), and since \(f(x)\) involves \(B\) and \(A\), the gradient of \(\mathcal{L}\) with respect to \(B\) or \(A\) is written as:

\[\nabla_{B_n}\mathcal{L} = \nabla_{f(x_n)}\mathcal{L} \cdot \nabla_{B_n}\mathcal{f(x_n)}\]

\[\nabla_{A_n}\mathcal{L} = \nabla_{f(x_n)}\mathcal{L} \cdot \nabla_{A_n}\mathcal{f(x_n)}\]

In each case, \(\nabla_{f(x_n)}\mathcal{L}\) is given to us as \(v_n\).

When plugging in the matrix-vector product \(BAx\) into matrixcalculus.org I get the following result for the partial derivatives of \(BAx\) with respect to \(B\) or \(A\):

\[\frac{\partial}{\partial B}(B \cdot A \cdot x) = (A \cdot x)^T \otimes \mathbb{I}\]

\[\frac{\partial}{\partial A}(B \cdot A \cdot x) = x^T \otimes B\]

Where the \(\otimes\) symbol is the tensor product or Kronecker Product where you multiple each element of the first matrix by the second matrix—a very differently shaped result than anything in the rsLoRA proof

If \(A\) is an \(m \times n\) matrix and \(B\) is a \(p \times q\) matrix, then the Kronecker product \(A \otimes B\) is the \(pm \times qn\) block matrix.

This StackExchange solution’s first half also shows something similar but without enough explanation for me to understand it.

Based on this it’s unclear to me how \(\nabla_{B_n}\mathcal{f(x_n)}\) results in \(x_n^TA_n^T\) and \(\nabla_{A_n}\mathcal{f(x_n)}\) results in \(B_n^Tx_n^T\). I spent 5-6 hours googling, looking on YouTube and prompting Claude/ChatGPT and didn’t come away with much (other than confirming that I don’t know matrix calculus).

That being said, we can still look at the shapes of each matrix or vector and see how the different tranposing and placement of variables makes it all work.

In the rsLoRA paper:

\(B\) has the dimensions \(d_1 \times r\)

\(A\) has the dimensions \(r \times d_2\)

Therefore, the matrix product \(BA\) which is (\(d_1 \times r\)) \(\times\) (\(r \times d_2\)), has the dimension \(d_1 \times d_2\) (the \(r\)’s cancel out due to matrix multiplication).

Since \(x\) is multiplied by \(BA\) to get \(BAx\), and assuming \(x\) is a vector, it has the dimensions \(d_2 \times 1\) (since the first dimension of \(x\) has to be equal to the last dimension of \(BA\)).

Putting it all together, \(f(x) = BAx\) has the dimensions:

\((d_1 \times r) \times (r \times d_2) \times (d_2 \times 1) = d_1 \times 1\)

Note that the \(r\)’s cancel out as do the \(d_2\)’s.

I’ll now a similar dimensional analysis of the gradients of \(\mathcal{L}\) with respect to \(A\) and \(B\):

\[\nabla_{B_n}\mathcal{L} = \gamma_r v_n x_n^T A_n^T\]

The gradient \(\nabla_{B_n}\mathcal{L}\) must have the same dimensions as \(B\), (\(d_1 \times r\)), so that we can make the gradient update to each element of \(B\). Similarly, \(v_n\) has to have the same dimensions as \(f(x)\), (\(d_1 \times 1\)).

\[(d_1 \times r) = (d_1 \times 1) \times (1 \times d_2) \times (d_2 \times r)\]

The \(1\)’sand the \(d_2\)’s cancel out in the matrix multiplication, so we get:

\[(d_1 \times r) = (d_1 \times r)\]

The dimensions match.

Similarly for the gradient of \(\mathcal{L}\) with respect to \(A\), the dimensions of the gradient must equal the dimensions of \(A\) (in order to do the gradient update):

\[\nabla_{A_n}\mathcal{L} = \gamma_r B_n^T v_n x_n^T\]

\[(r \times d_2) = (r \times d_1) \times (d_1 \times 1) \times(1 \times d_2)\]

\[(r \times d_2) = (r \times d_2)\]

The dimensions match.

The \(d_1\)’s and the \(1\)’s cancel out due to matrix multiplication.

Adapter Value after \(n\) Updates

I struggled with this section so the following is just me thinking out loud and may not help clarify your understanding.

As a reminder, here are the expressions for the gradient of Loss with respect to the adapters \(A_n\) and \(B_n\) (where \(n\) is the number of gradient updates during training):

\[\nabla_{B_n}\mathcal{L} = \gamma_r v_n x_n^T A_n^T\]

\[\nabla_{A_n}\mathcal{L} = \gamma_r B_n^T v_n x_n^T\]

After \(n \ge 1\) SGD updates (in each update, we are subtracting from the adapter the learning rate times the gradient of the Loss with respect to the adapter) the two adapters \(B_n\) and \(A_n\) look like:

\[B_n = (-\eta \gamma_r \sum_{k=0}^{n-1}v_kx_k^T + \mathcal{O}_r(\gamma_r^2))A_0^T\]

\[A_n =A_0(1 + \mathcal{O}_r(\gamma_r^2))\]

Note that \(B\) is initialized as a 0-matrix so there’s no \(B_0\) in their expression.

Three observations:

- Though the gradient of Loss wrt \(B_n\) contains an \(A_n\) term (\(\gamma_rv_nx_n^TA_n^T\)), the expression here for \(B_n\) contains an \(A_0\) term.

- The expression here for \(A_n\) does not include the gradient terms (\(\gamma_r v_nx_n^TA_n^T\)).

- There is an \(\mathcal{O}_r(\gamma_r^2)\) term in both the \(B_n\) and \(A_n\) expressions.

From those observations I’m coming to the following three conclusions (with the help of Claude):

- The term \(\mathcal{O}_r(\gamma_r^2)\), which is in Big-O notation, represents some term(s) that has an upper bound of \(\gamma_r^2\) (in other words, some constant term). I’m not sure what term they actually represent—maybe some error term? I don’t know.

- \(A_n\) is a function of \(A_0\) and the constant term \(\mathcal{O}_r(\gamma_r^2)\). I wonder if that’s because \(A_0\) is initialized as a normal (Gaussian) matrix and since it’s a rank-stable adapter, it doesn’t deviate that much from that normal distribution? Again, not sure. Additionally, in their \(B_n\) expression they multiply by \(A_0^T\) instead of the \(A_n^T\) term in the gradient—maybe an indication that \(A_n\) doesn’t deviate much from \(A_0\)? Not sure.

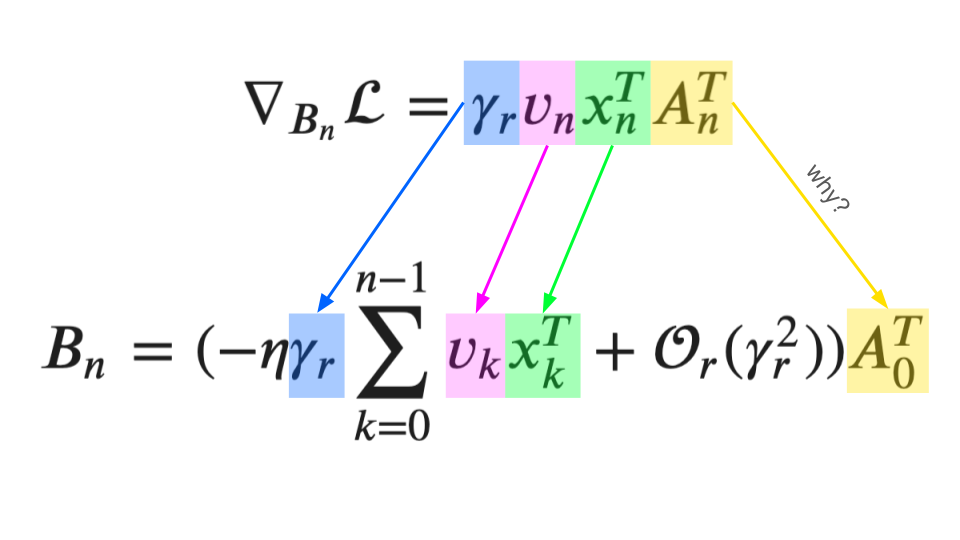

A supplementary graphic I created to try to illustrate my thinking + confusion:

UPDATE: A fastai study group member provided the following insight which now clearly explains why \(B_n\) is written in terms of \(A_0\). It’s because the derative of \(A_n\) has a \(B_n\) term in it (\(\nabla_{A_n} = \gamma_rB_n^Tv_nX_n^T\)) and one step after initialization (\(n=1\)), \(B_1\) is written in terms of \(A_0\):

\(n=0\):

\[B_n = 0\] \[A_n = A_0\]

\[\nabla_{B_0}\mathcal{L}=\gamma_rv_0x_0^TA_0^T\]

\[\nabla_{A_0}\mathcal{L}=\gamma_rB_0^Tv_0x_0^T = 0\]

\(n=1\):

\[B_1 = 0 - \gamma_rv_0x_0^TA_0^T\]

\[A_1 = A_0 - 0 = A_0\]

\[\nabla_{B_1}\mathcal{L}=\gamma_rv_1x_1^TA_1^T = \gamma_rv_1x_1^TA_0^T\]

\[\nabla_{A_1}\mathcal{L}=\gamma_rB_1^Tv_1x_1^T = \gamma_r(\gamma_rv_0x_0^TA_0^T)^Tv_1x_1^T\]

Notice how \(B_1\) has an \(A_0\) term in it. Similarly \(\nabla_{A_1}\mathcal{L}\) is in terms of \(A_0\) as well since \(B_1\) is in terms of \(A_0\).

Deriving Stable Rank

Let’s just take their expressions of \(B_n\) and \(A_n\) for granted and continue with the derivation of the stable rank condition:

\[B_n = (-\eta \gamma_r \sum_{k=0}^{n-1}v_kx_k^T + \mathcal{O}_r(\gamma_r^2))A_0^T\]

\[A_n =A_0(1 + \mathcal{O}_r(\gamma_r^2))\]

Then \(\gamma_rB_nA_n\) is:

\[\gamma_rB_nA_n = -\gamma_r^2\eta\sum_{k=0}^{n-1}v_kx^T_kA^T_0A_0 + \mathcal{O}_r(\gamma_r^3)A_0^TA_0\]

To try and derive this result, I’ll start with \(B_n\) and expand \(B_n\) by multiplying the terms inside the parentheses by \(A_0^T\):

\[B_n = \big(-\eta \gamma_r \sum_{k=0}^{n-1}v_kx_k^T + \mathcal{O}_r(\gamma_r^2)\big)A_0^T = -\eta \gamma_r \sum_{k=0}^{n-1}v_kx_k^TA_0^T + \mathcal{O}_r(\gamma_r^2)A_0^T\]

I’ll then expand \(A_n\) by multiplying the terms inside the parentheses by \(A_0\):

\[A_n =A_0(1 + \mathcal{O}_r(\gamma_r^2)) = A_0 + A_0\mathcal{O}_r(\gamma_r^2)\]

Then, I’ll write out the full multiplication of \(\gamma_rB_nA_n\):

\[\gamma_rB_nA_n = \big[ \gamma_r \big] \times \big[-\eta \gamma_r \sum_{k=0}^{n-1}v_kx_k^TA_0^T + \mathcal{O}_r(\gamma_r^2)A_0^T\big] \times \big[ A_0 + A_0\mathcal{O}_r(\gamma_r^2) \big]\]

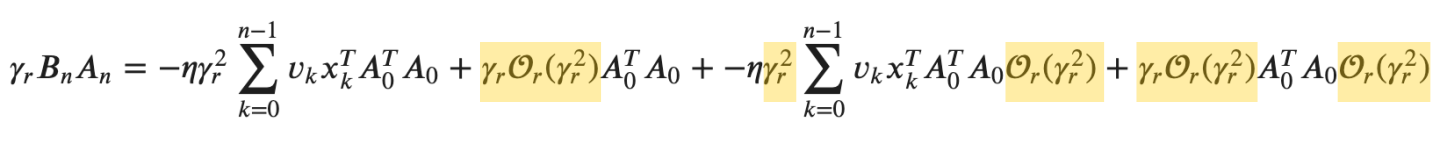

\(B_n\) is getting multiplied by two terms, \(A_0\) and \(A_0\mathcal{O}_r(\gamma_r^2)\). Doing that multiplication and expanding it out:

\[\gamma_rB_nA_n = \big[ \gamma_r \big] \times \big[ -\eta \gamma_r \sum_{k=0}^{n-1}v_kx_k^TA_0^TA_0 + \mathcal{O}_r(\gamma_r^2)A_0^TA_0 + -\eta \gamma_r \sum_{k=0}^{n-1}v_kx_k^TA_0^TA_0\mathcal{O}_r(\gamma_r^2) + \mathcal{O}_r(\gamma_r^2)A_0^TA_0\mathcal{O}_r(\gamma_r^2) \big]\]

Now I’ll multiple the \(\gamma_r\) term at the start into the giant second term:

\[\gamma_rB_nA_n = -\eta \gamma_r^2 \sum_{k=0}^{n-1}v_kx_k^TA_0^TA_0 + \gamma_r\mathcal{O}_r(\gamma_r^2)A_0^TA_0 + -\eta \gamma_r^2 \sum_{k=0}^{n-1}v_kx_k^TA_0^TA_0\mathcal{O}_r(\gamma_r^2) + \gamma_r\mathcal{O}_r(\gamma_r^2)A_0^TA_0\mathcal{O}_r(\gamma_r^2)\]

Next, I’ll highlight terms where \(\gamma_r\) is multiplied by \(\mathcal{O}_r(\gamma_r^2)\):

The first highlighted term, \(\gamma_r\mathcal{O}_r(\gamma_r^2)\) becomes \(\mathcal{O}_r(\gamma_r^3)\).

The second (\(\gamma_r^2\)) and third (\(\mathcal{O}_r(\gamma_r^2)\)) highlighted terms multiply to become \(\mathcal{O}_r(\gamma_r^4)\).

The fourth (\(\gamma_r\mathcal{O}_r(\gamma_r^2)\)) and fifth (\(\mathcal{O}_r(\gamma_r^2)\)) highlighted terms multiply to become \(\mathcal{O}_r(\gamma_r^5)\).

Rewriting the expression with those simplifications:

\[\gamma_rB_nA_n = -\eta \gamma_r^2 \sum_{k=0}^{n-1}v_kx_k^TA_0^TA_0 + \mathcal{O}_r(\gamma_r^3)A_0^TA_0 + -\eta \sum_{k=0}^{n-1}v_kx_k^TA_0^TA_0\mathcal{O}_r(\gamma_r^4) + A_0^TA_0\mathcal{O}_r(\gamma_r^5)\]

According to what I understood from prompting Claude, the last two terms, \(-\eta \sum_{k=0}^{n-1}v_kx_k^TA_0^TA_0\mathcal{O}_r(\gamma_r^4) + A_0^TA_0\mathcal{O}_r(\gamma_r^5)\) are encompassed by the earlier \(\mathcal{O}_r(\gamma_r^3)\) term. The reason being that since \(\gamma_r\) goes to \(0\) (as \(r\) goes to \(\infty\)) as stated at the beginning of Theorem 3.2, the term \(\mathcal{O}_r(\gamma_r^3)\), where \(\gamma_r^3\) the upper bound, will always be larger than \(\mathcal{O}_r(\gamma_r^4)\) or \(\mathcal{O}_r(\gamma_r^5)\).

As \(\gamma_r\) goes to \(0\), \(\gamma_r^3 \gt \gamma_r^4 \gt \gamma_r^5\).

So with the \(\mathcal{O}_r(\gamma_r^4)\) and \(\mathcal{O}_r(\gamma_r^5)\) getting swallowed by the \(\mathcal{O}_r(\gamma_r^3)\) term, rewriting the expression gives us:

\[\gamma_rB_nA_n = -\eta \gamma_r^2 \sum_{k=0}^{n-1}v_kx_k^TA_0^TA_0 + \mathcal{O}_r(\gamma_r^3)A_0^TA_0\]

Which is the expression in Equation (8) of the rsLoRA paper.

Next they define the expectation of the initialiation \(A_0\) as:

\[E_{A_0}(A_0^TA_0) = r\sigma_AI_{d \times d}\]

and replace \(A_0^TA_0\) with \(r\sigma_AI_{d \times d}\) in the expression of \(\gamma_rB_nA_n\):

\[\gamma_rB_nA_n = -\eta \gamma_r^2 \sum_{k=0}^{n-1}v_kx_k^TA_0^TA_0 + \mathcal{O}_r(\gamma_r^3)A_0^TA_0 = -\eta \gamma_r^2 \sum_{k=0}^{n-1}v_kx_k^Tr\sigma_AI_{d \times d} + \mathcal{O}_r(\gamma_r^3)r\sigma_AI_{d \times d}\]

I think the last term, \(\mathcal{O}_r(\gamma_r^3)r\sigma_AI_{d \times d}\) gets simplified to \(\mathcal{O}_r(\gamma_r^3)\), and multipling by the identity matrix \(I_{d \times d}\) is like multiplying by \(1\), so we end up with Equation (9) in the rsLoRA paper:

\[\gamma_rB_nA_n = -\gamma_r^2 r\sigma_A \eta\sum_{k=0}^{n-1}v_kx_k^T + \mathcal{O}_r(\gamma_r^3)\]

I’m very fuzzy on the final steps, but taking a shot at explaining how I understand it:

Condition 1 of Definition 3.1 states:

- If the inputs to the adapter are iid such that the \(m\)’th moment is \(\Theta_r(1)\) in each entry, then the \(m\)’th moment of the outputs of the adapter is also \(\Theta_r(1)\) in each entry.

The forward pass through the adapters is \(\gamma_rB_nA_nx_n\).

The \(m\)’th moment of the iid inputs is represented by the expression:

\[E_x((x_k^Tx_n)^m) \in \Theta_r(1)\]

Where does the term \(E_x((x_k^Tx_n)^m)\) comes from? I think it comes from Equation (11). First I’ll write Equation (9) again for reference:

\[\gamma_rB_nA_n = -\gamma_r^2 r\sigma_A \eta\sum_{k=0}^{n-1}v_kx_k^T + \mathcal{O}_r(\gamma_r^3)\]

The forward pass multiplies Equation (9) by the new input \(x_n\) to get something like this (not shown in the paper, my assumption):

\[\gamma_rB_nA_nx_n = -\gamma_r^2 r\sigma_A \eta\sum_{k=0}^{n-1}v_kx_k^Tx_n + \mathcal{O}_r(\gamma_r^3)\]

Note that we now have a \(x_k^Tx_n\) term inside the summation.

Let’s look at just the left-hand side of Equation (11) now:

\[E_{x,A_0}((\gamma_rB_nA_nx_n)^m)\]

This is the expression for \(m\)’th moment of the forward pass (if I understand correctly).

Looking at the whole Equation (11):

\[E_{x,A_0}((\gamma_r B_n A_n x_n)^m) = (-\gamma_r^2r\sigma_A\eta)^m\sum_{k=0}^{n-1}v_k^mE_x((x_k^Tx_n)^m) + \Theta_r((\gamma_r^3r)^m) \in \Theta_r((\gamma_r^2r)^m)\]

Everything on the right-hand side of the equation is raised to the power of \(m\):

- \((-\gamma_r^2r\sigma_A\eta)^m\)

- \(v_k^m\)

- \((x_k^Tx_n)^m\)

- \(\Theta_r((\gamma_r^3r)^m)\)

The expected value is taken of \(x\) and \(A_0\). We already took care of the expectation of \(A_0\) earlier with the term \(r\sigma_A\). Equation (11) takes care of the expectation of \(x\) with the term \(E_x((x_k^Tx_n)^m)\). At least that’s my understanding.

Finally the stuff at the end:

\[\in \Theta_r((\gamma_r^2r)^m)\]

Is saying that this expected value \(E_{x,A_0}\) is in the set of values bound above and below by \((\gamma_r^2r)^m\). Why? Well there are two \(\gamma_r\) terms in \(E_{x,A_0}\):

\((\gamma_r^2r\sigma_A\eta)^m\)

and

\(\Theta_r((\gamma_r^3r)^m)\)

I think it’s correct to say that the term \((\gamma_r^2r\sigma_A\eta)^m\) is in the set \(\Theta_r((\gamma_r^2r)^m)\) (in other words it’s bound above and below by a constant times \((\gamma_r^2r)^m\)).

\(\Theta_r((\gamma_r^2r)^m)\) encompasses \(\Theta_r((\gamma_r^3r)^m)\) since as \(\gamma_r\) goes to \(0\) (an initial assumption of Theorem 3.2), \(\gamma_r^2 \gt \gamma_r^3\).

Definition 3.1 stated that the \(m\)’th moments of the adapter output have to be in the set \(\Theta_r(1)\) for the adapters to be considered rank-stable.

If the \(m\)’th moment, \(E_{x,A_0}((\gamma_r B_n A_n x_n)^m)\), is in the set \(\Theta_r((\gamma_r^2r)^m)\) (as is defined in Equation (11)) and if Definition 3.1 condition is to be satisfied, the set \(\Theta_r((\gamma_r^2r)^m)\) must be equal to \(\Theta_r(1)\):

\(\Theta_r((\gamma_r^2r)^m)\) = \(\Theta_r(1)\)

Equating the terms inside the \(\Theta_r\) on each side:

\((\gamma_r^2r)^m = 1\)

Raising each side to \(\frac{1}{m}\) (to get rid of the \(m\) exponent on the left) gives us:

\(\gamma_r^2r = 1\)

Dividing both sides by \(r\):

\(\gamma_r^2 = \frac{1}{r}\)

Taking the square root of both sides:

\(\gamma_r = \frac{1}{\sqrt{r}}\)

Which is the proof that in order for the adapters to have stable outputs the value of \(\gamma_r\) must be a constant of \(\frac{1}{\sqrt{r}}\) or in other words:

\[\gamma_r \in \Theta_r(\frac{1}{\sqrt{r}})\]

I don’t understand how they derived Equation (10) so I’m not going to write about it here.