WebGPU Puzzles: Walk through of Official Solutions

Background

This file contains my walkthrough of the official WebGPU Puzzle solutions that I found challenging to understand and/or critical in helping me understand core concepts of GPU programming. You can find the Excel spreadsheet with my solution visualizations here. The WebGPU puzzles are published by Answer.AI at https://gpupuzzles.answer.ai/puzzles.

Puzzle 7

@group(0) @binding(0) var<storage, read_write> a : array<f32>;

@group(0) @binding(1) var<storage, read_write> out : array<f32>;

const wgs = vec3({{workgroupSize}}); // workgroup sizes

const twg = vec3({{totalWorkgroups}}); // total workgroups

@compute @workgroup_size({{workgroupSize}})

fn main(@builtin(local_invocation_id) lid: vec3<u32>,

@builtin(global_invocation_id) gid: vec3<u32>,

@builtin(workgroup_id) wid: vec3<u32>

) {

let wgSize: u32 = wgs.x * wgs.y * wgs.z;

let wg = wid.x + wid.y * twg.x;

let i = lid.x + lid.y * wgs.x + wg * wgSize;

out[i] = a[i] + 10;

}___________________________________

Test case 1

Workgroup Size ( 2, 2, 1 )

Total Workgroups ( 2, 2, 1 )

Input a [ 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 ]

Expected [ 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 ]

___________________________________

Test case 2

Workgroup Size ( 2, 2, 1 )

Total Workgroups ( 3, 3, 1 )

Input a [ 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 ]

Expected [ 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 ]I actually didn’t quite understand this solution until I revisited it while I was working on Puzzle #14 after I recalled that this solution dealt with situations where the number of threads in a workgroup was less than the number of positions in the input array.

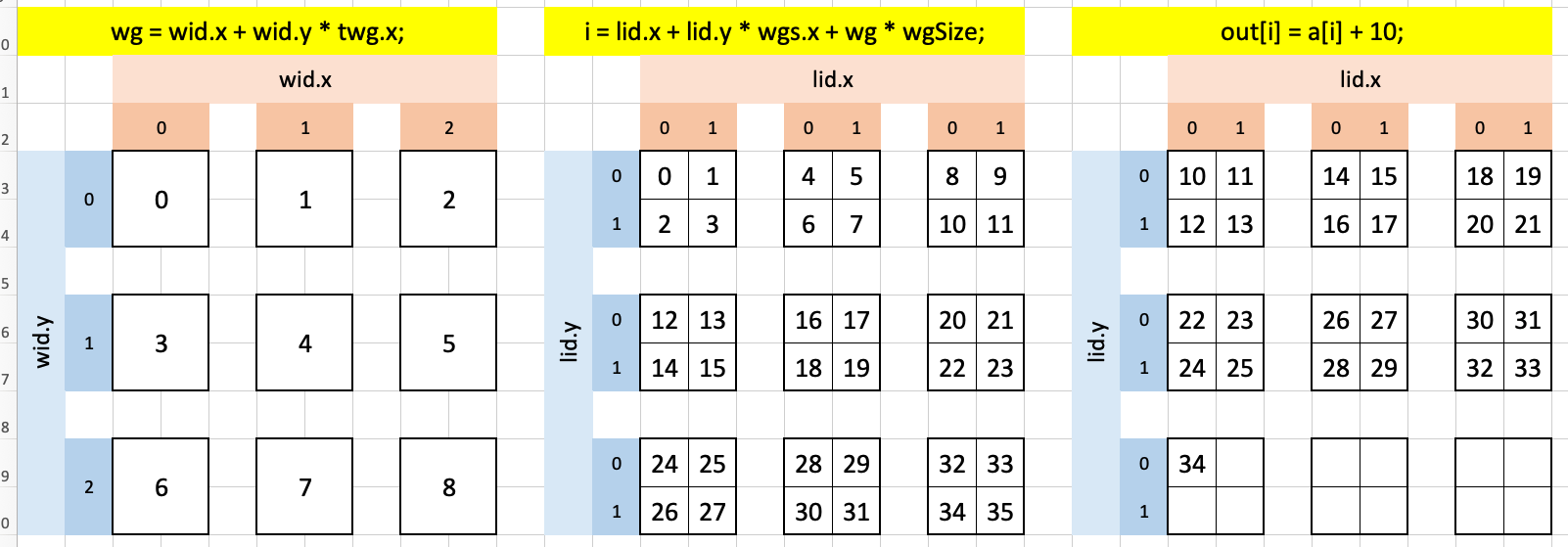

I interpret wg as being the global “workgroup indexer” and i as the global “thread indexer.” In wg, the value of wid.x (0, 1, 2) is incremented by 1 as you go down wid.y by the term wid.y * twg.x. Similarly for i, lid.y * wgs.x increments the index by 1 as you go down lid.y while wg * wgSize increments the i by 4 as you traverse over the wg index of the workgroup. In this way, while no single workgroup can handle all 25 elements of the input array, spreading them out across 9 workgroups make this light work.

Puzzle 8

This puzzle also had fewer threads per block than number of elements in the input array.

@group(0) @binding(0) var<storage, read_write> a : array<f32>;

@group(0) @binding(1) var<storage, read_write> out : array<f32>;

// workgroup sizes x, y, z

const wgs = vec3({{workgroupSize}});

// total workgroups x, y, z

const twg = vec3({{totalWorkgroups}});

// flat shared memory array

var<workgroup> smem: array<f32, {{smemSize}}>;

@compute @workgroup_size({{workgroupSize}})

fn main(@builtin(local_invocation_id) lid: vec3<u32>,

@builtin(global_invocation_id) gid: vec3<u32>,

@builtin(workgroup_id) wid: vec3<u32>) {

if (gid.x < arrayLength(&a)) {

smem[lid.x] = a[gid.x];

}

workgroupBarrier();

out[gid.x] = smem[lid.x] + 10;

}___________________________________

Test case 1

Workgroup Size ( 4, 1, 1 )

Total Workgroups ( 2, 1, 1 )

Shared Memory Size ( 8, 1, 1 )

Input a [ 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 ]

Expected [ 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 ]

___________________________________

Test case 2

Workgroup Size ( 8, 1, 1 )

Total Workgroups ( 2, 1, 1 )

Shared Memory Size ( 8, 1, 1 )

Input a [ 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 ]

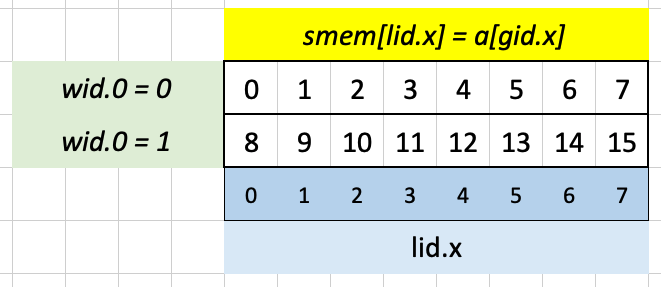

Expected [ 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 ]The following lines load the input array into shared memory:

if (gid.x < arrayLength(&a)) {

smem[lid.x] = a[gid.x];

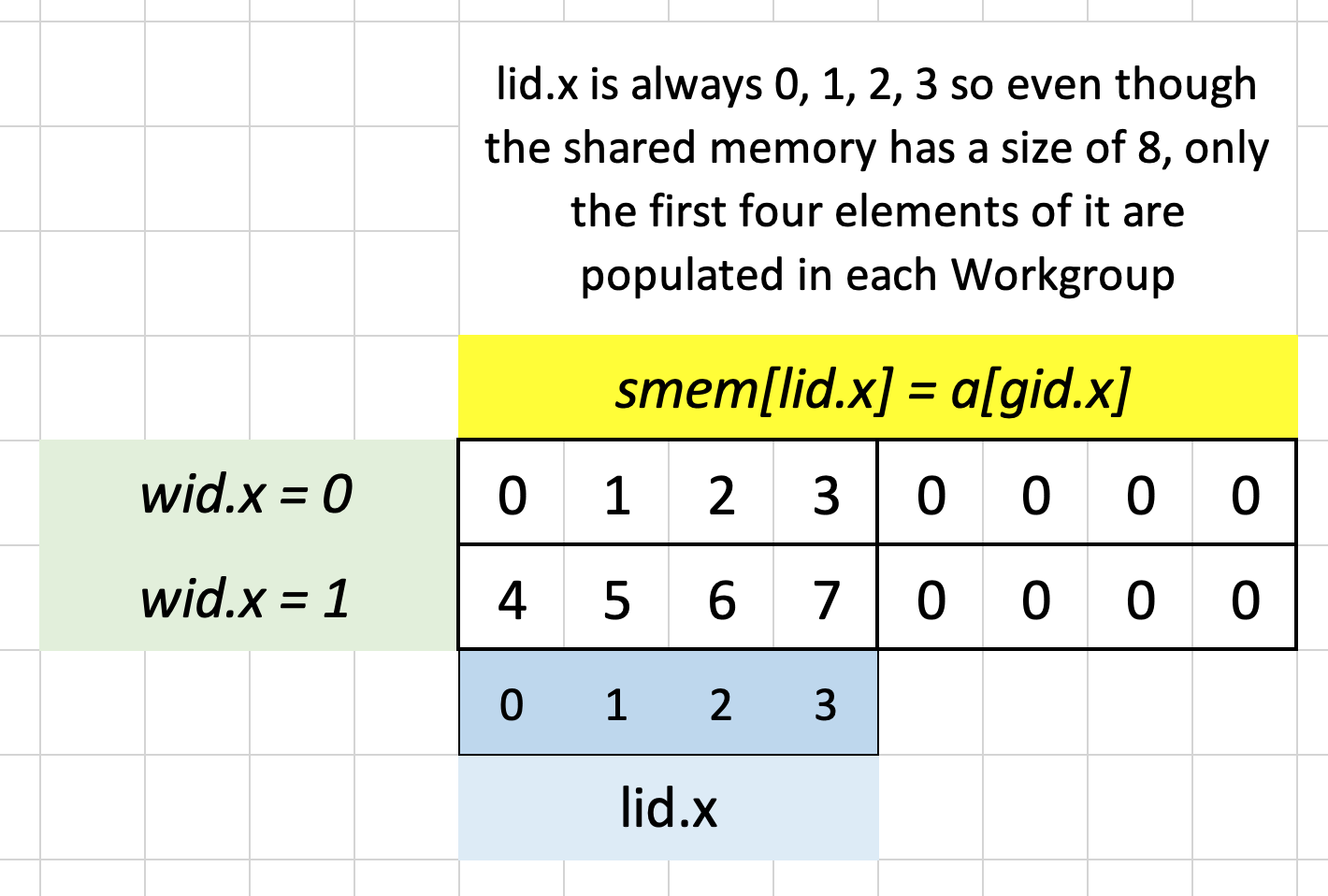

}Visualizing Test Case 1: in each workgroup, since lid.x is (0, 1, 2, 3), only the first four elements of shared memory are filled with data. In the first workgroup, gid.x is (0, 1, 2, 3) and in the second workgroup, it’s (4, 5, 6, 7) so the corresponding elements of input array a are loaded into shared memory.

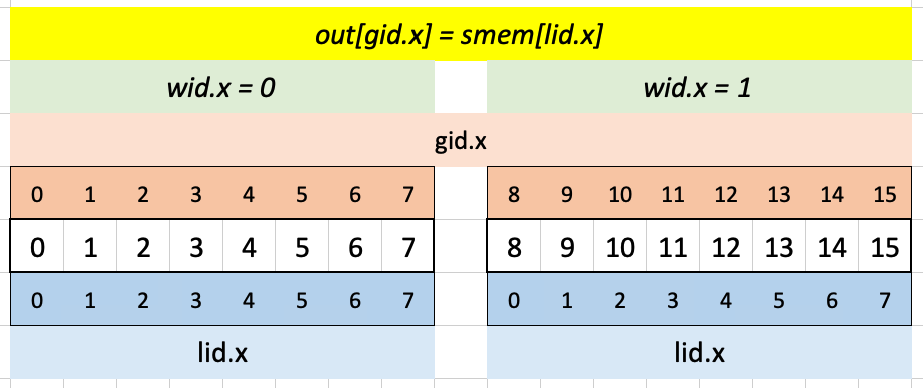

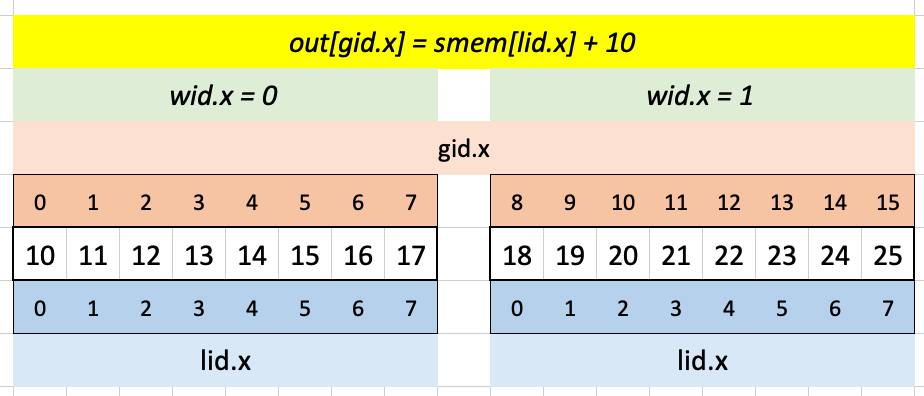

The following line assigns to out in each workgroup the first four elements of smem:

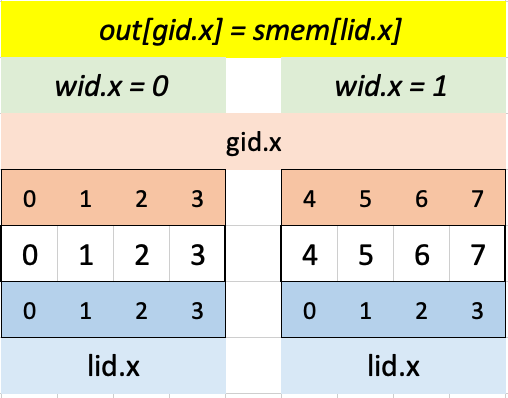

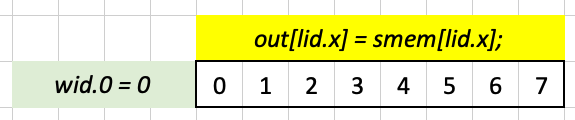

out[gid.x] = smem[lid.x];Visualizing that in Excel for Test Case 1:

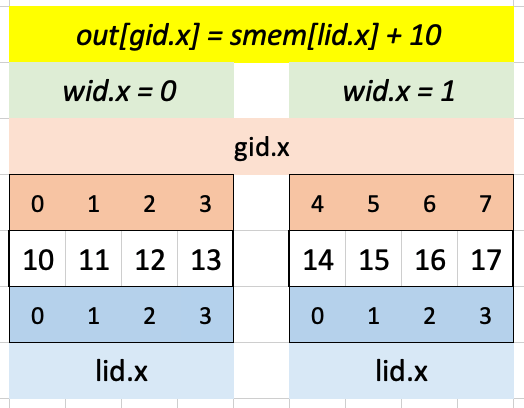

lid.x is always (0, 1, 2, 3) so the first four elements of smem are always indexed. gid.x is (0, 1, 2, 3) for wid.x = 0 and (4, 5, 6, 7) for wid.x = 1 so the first four elements of out are loaded with the first four elements of smem for the first workgroup and the second four elements of out are loaded with the first four elements of smem for the second workgroup. Adding 10 to smem values gives the expected output:

out[gid.x] = smem[lid.x];Here are is the solution visualized for Test Case 2:

The full 8-element shared memory array is filled with values from the 16-element input array a:

Again lid.x is equal in both workgroups, so the first 8 elements of smem are loaded into the corresponding sequence of 8 elements in out using gid.x:

Adding 10 to the smem values yields the expected result:

Puzzle 9

@group(0) @binding(0) var<storage, read_write> a : array<f32>;

@group(0) @binding(1) var<storage, read_write> out : array<f32>;

const wgs = vec3({{workgroupSize}}); // workgroup sizes

const twg = vec3({{totalWorkgroups}}); // total workgroups

var<workgroup> smem: array<f32, {{smemSize}}>;

@compute @workgroup_size({{workgroupSize}})

fn main(@builtin(local_invocation_id) lid: vec3<u32>,

@builtin(global_invocation_id) gid: vec3<u32>,

@builtin(workgroup_id) wid: vec3<u32>

) {

let i = lid.x + lid.y * wgs.x;

smem[lid.x] = a[i];

workgroupBarrier();

out[lid.x] = smem[lid.x];

if (lid.x > 0) {

out[lid.x] += smem[lid.x - 1];

if (lid.x > 1) {

out[lid.x] += smem[lid.x - 2];

}

}

}___________________________________

Test case 1

Workgroup Size ( 8, 1, 1 )

Total Workgroups ( 1, 1, 1 )

Shared Memory Size ( 8, 1, 1 )

Input a [ 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 ]

Expected [ 0 1 3 6 9 12 15 18 ]

___________________________________

Test case 2

Workgroup Size ( 10, 1, 1 )

Total Workgroups ( 1, 1, 1 )

Shared Memory Size ( 10, 1, 1 )

Input a [ 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 ]

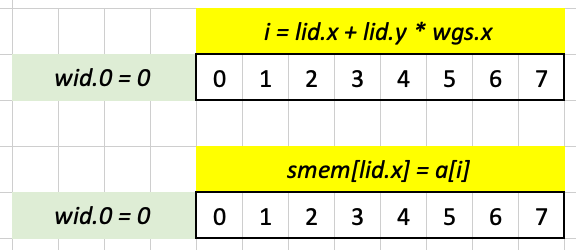

Expected [ 0 1 3 6 9 12 15 18 21 24 ]Since we have only one workgroup with size (8, 1, 1) in Test Case 1, wgs.x is 0 and lid.y is 0, so i ends up being equal to lid.x. The shared memory array smem has the same size as the input array a (and the workgroup) so smem[lid.x] = a[i] loads in the entire array a into shared memory.

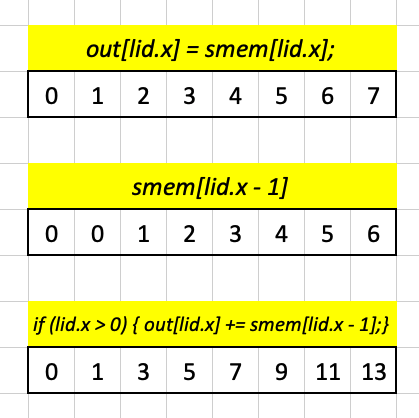

Next, we load into out the entire array smem with the following line:

out[lid.x] = smem[lid.x];Our goal is to “sum together the last 3 positions of a and store it in out.” To do this, we first “slide” or “shift” smem one element to the right with the code smem[lid.x - 1], and add it to out. We only do this for i values above 0 since we don’t want to index into smem with -1:

We shift smem by 2 elements to the right (again only doing it for i values that won’t result in a negative index, i > 1) and add that to out to get our expected result:

Puzzle 10

@group(0) @binding(0) var<storage, read_write> a : array<f32>;

@group(0) @binding(1) var<storage, read_write> b : array<f32>;

@group(0) @binding(2) var<storage, read_write> out : array<f32>;

const wgs = vec3({{workgroupSize}});

const twg = vec3({{totalWorkgroups}});

var<workgroup> smem: array<f32, {{smemSize}}>;

@compute @workgroup_size({{workgroupSize}})

fn main(@builtin(local_invocation_id) lid: vec3<u32>,

@builtin(global_invocation_id) gid: vec3<u32>) {

// assumes wgs.x > arrayLength(&a);

smem[lid.x] = a[gid.x] * b[gid.x];

workgroupBarrier();

if (gid.x == 0) {

for (var i: u32=0; i<arrayLength(&a); i+=1) {

out[0] += smem[i];

}

}

}___________________________________

Test case 1

Workgroup Size ( 4, 1, 1 )

Total Workgroups ( 1, 1, 1 )

Shared Memory Size ( 4, 1, 1 )

Input a [ 0 1 2 3 ]

Input b [ 0 1 2 3 ]

Expected [ 14 ]

___________________________________

Test case 2

Workgroup Size ( 5, 1, 1 )

Total Workgroups ( 1, 1, 1 )

Shared Memory Size ( 5, 1, 1 )

Input a [ 0 1 2 3 4 ]

Input b [ 0 1 2 3 4 ]

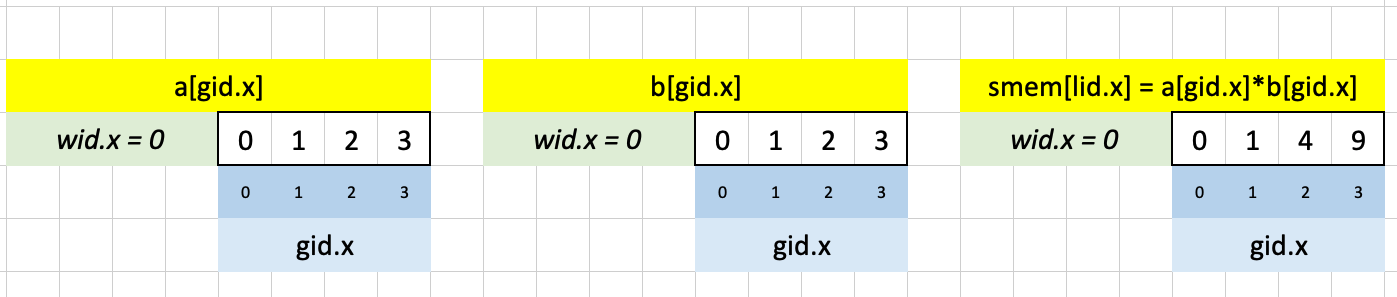

Expected [ 30 ]To take the dot product between two 1-D array, we need to take their cumulative element-wise sum. The official solution starts by loading these element-wise sums into shared memory with:

smem[lid.x] = a[gid.x] * b[gid.x];After that, we simply iterate through the shared memory array and accumulate the sum with:

if (gid.x == 0) {

for (var i: u32=0; i<arrayLength(&a); i+=1) {

out[0] += smem[i];

}

}IIUC, the guard if (gid.x == 0) prevents more than one thread from working on this task.

Puzzle 11

@group(0) @binding(0) var<storage, read_write> a : array<f32>;

@group(0) @binding(1) var<storage, read_write> b : array<f32>;

@group(0) @binding(2) var<storage, read_write> out : array<f32>;

const wgs = vec3({{workgroupSize}});

const twg = vec3({{totalWorkgroups}});

var<workgroup> smemA: array<f32, wgs.x * wgs.y * wgs.z + 4>;

var<workgroup> smemB: array<f32, 4>;

@compute @workgroup_size({{workgroupSize}})

fn main(@builtin(local_invocation_id) lid: vec3<u32>,

@builtin(global_invocation_id) gid: vec3<u32>,

@builtin(workgroup_id) wid: vec3<u32>

) {

// Each workgroup is responsible computes total workgroup size

// values of out and caches total workgroup size + 4 values

// of a

let wgSize: u32 = wgs.x; // assumes wgs.y = wgs.z = 1

smemA[lid.x] = a[gid.x];

if (lid.x < 4) {

smemB[lid.x] = b[lid.x];

if (wid.x * wgSize + wgSize + lid.x < arrayLength(&a)) {

smemA[wgSize + lid.x] =

a[wid.x * wgSize + wgSize + lid.x];

} else {

smemA[wgSize + lid.x] = 0.0;

}

}

workgroupBarrier();

var sum: f32 = 0.0;

for (var i: u32 = 0; i < 4; i += 1) {

if (gid.x + i < arrayLength(&a)) {

sum = sum + smemA[lid.x + i] * smemB[i];

}

}

out[gid.x] = sum;

}___________________________________

Test case 1

Workgroup Size ( 8, 1, 1 )

Total Workgroups ( 2, 1, 1 )

Shared Memory Size ( 12, 1, 1 )

Input a [ 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 ]

Input b [ 0 1 2 3 ]

Expected [ 14 20 26 32 38 44 50 56 62 68 74 80 41 14 0 ]

___________________________________

Test case 2

Workgroup Size ( 8, 1, 1 )

Total Workgroups ( 3, 1, 1 )

Shared Memory Size ( 12, 1, 1 )

Input a [ 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 ]

Input b [ 0 1 2 3 ]

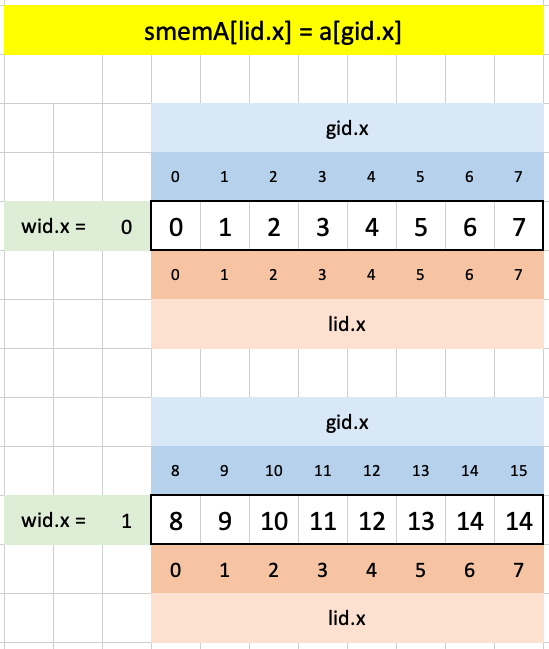

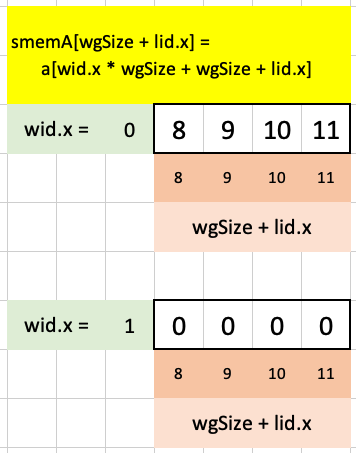

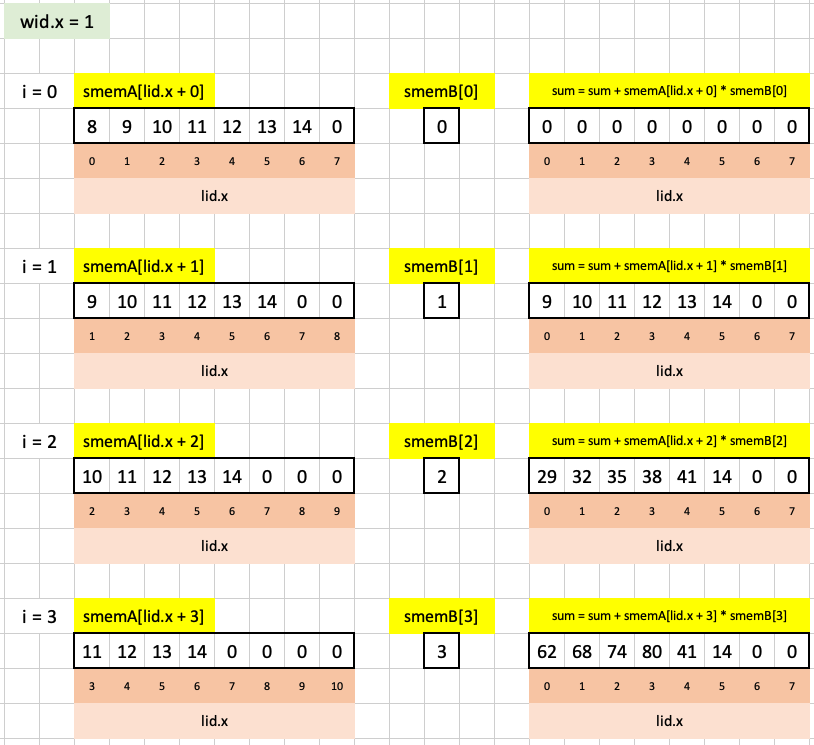

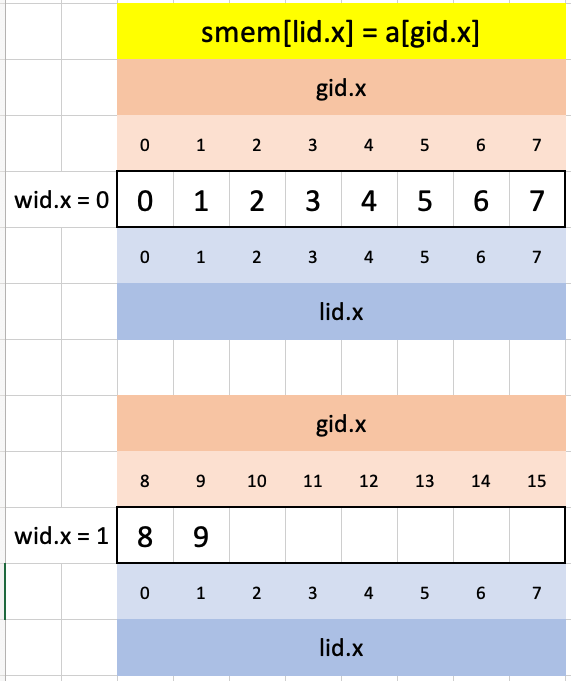

Expected [ 14 20 26 32 38 44 50 56 62 68 74 80 86 92 98 50 17 0 ]In Test case 1, our workgroup has 8 threads, our shared memory arrays have 12 spots, and our input has 15 elements. We start by loading the first 8 elements of a into smemA with lid.x and gid.x:

smemA[lid.x] = a[gid.x];Here’s what that looks like in Excel. Each workgroup gets assigned its consecutive sequence of 8 elements:

Next, to load in the remaining 4 elements of a into smemA and all four elements of b into smemB we run the following code:

if (lid.x < 4) {

smemB[lid.x] = b[lid.x];

if (wid.x * wgSize + wgSize + lid.x < arrayLength(&a)) {

smemA[wgSize + lid.x] = a[wid.x * wgSize + wgSize + lid.x];

} else {

smemA[wgSize + lid.x] = 0.0;

}

}The guard lid.x < 4 ensures that we are only handling 4 elements at a time. The next line is simple, and loads the full contents of b into smemB:

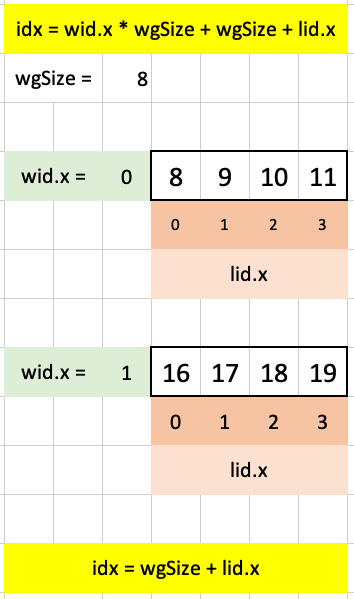

smemB[lid.x] = b[lid.x];Now we get into some more tricky stuff to assign the correct set of 4 final elements to shared memory in the appropriate workgroup. Let’s first visulize the more involved index (where wgSize is wgs.x which is 8 in Test case 1):

wid.x * wgSize + wgSize + lid.xVisualizing this index in Excel for each workgroup, noting that it’s restricted to 4 elements (due to our guard lid.x < 4) as it builds off lid.x:

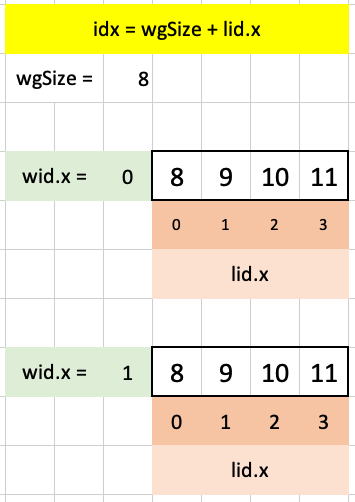

The other index that we use is wgSize + lid.x which is more straightforward (it adds 8 to each of the four elements of lid.x):

This index will be used to extend the index into the lat 4 elements of shared memory array past the 8 elements available in lid.x or gid.x for each workgroup with the following code:

if (wid.x * wgSize + wgSize + lid.x < arrayLength(&a)) {

smemA[wgSize + lid.x] = a[wid.x * wgSize + wgSize + lid.x];

} else {

smemA[wgSize + lid.x] = 0.0;

}For the first workgroup, the maximum value of wid.x * wgSize + wgSize + lid.x is less than arrayLength(&a) so we load in the 9th to 12th elements of a into smemA. For the second workgroup, the maximum value of wid.x * wgSize + wgSize + lid.x is more than arrayLength(&a) so we assign 0s:

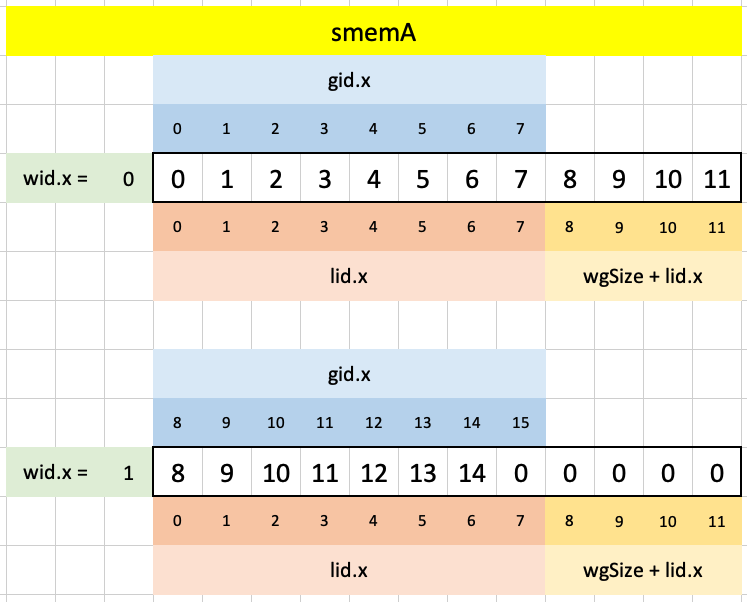

In this way, we have assigned a maximum of 12 elements of a into smemA, extending the available indexes gid.x and lid.x past their maximum of 8 elements using wid.x and wgs.x:

With our data loaded into shared memory arrays we can now go about performing 1-D convolution between a and b with the following code:

var sum: f32 = 0.0;

for (var i: u32 = 0; i < 4; i += 1) {

if (gid.x + i < arrayLength(&a)) {

sum = sum + smemA[lid.x + i] * smemB[i];

}

}

out[gid.x] = sum;Understanding this loop was a pivotal point in my understanding of parallelism. While we are iterating over i which is a 32-bit unsigned integer, we are performing 8 element-wise operations in each loop iteration at the same time (since we are using lid.x to index into smemA) in each workgroup (which is why we use gid.x to index into out to assign the correct value of sum).

What’s counterintuitive at first is that sum is a single f32 32-bit floating point number, but since we are using lid.x and gid.x it is being manipulated 16 different ways (8 threads across 2 workgroups). So although to me it initially looked like sum was behaving as an array, it’s not. The array-like behavior is the parallelism of the GPU.

The following line:

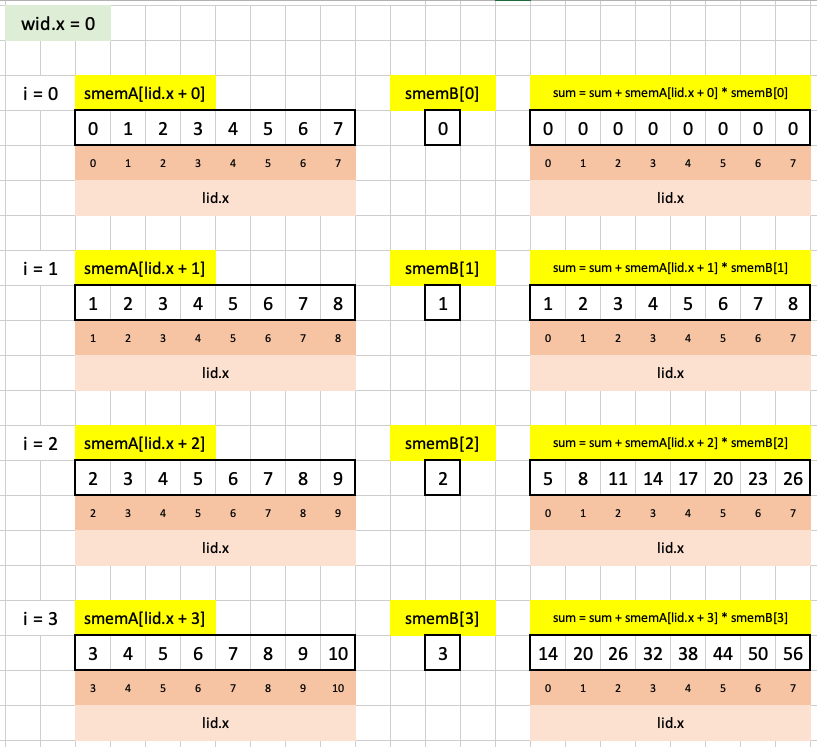

sum = sum + smemA[lid.x + i] * smemB[i];is visualized in Excel for the first workgroup as follows:

Note that in each iteration of the loop we are shifting smemA and smemB by 1 element to the left and taking the elementwise product (across 8 threads). From the individual thread’s perspective, it’s a product between two numbers, accumulating their sum over each loop iteration.

Here’s a visualization of the loop iterations in the second workgroup:

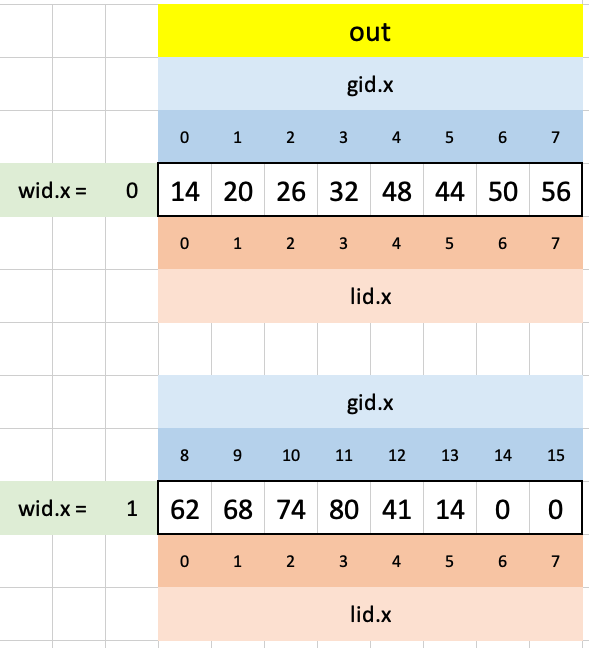

After each loop is finished, we assign the resulting number to its corresponding location in out to get our final result:

Puzzle 12

@group(0) @binding(0) var<storage, read_write> a : array<f32>;

@group(0) @binding(1) var<storage, read_write> out : array<f32>;

const wgs = vec3({{workgroupSize}});

const twg = vec3({{totalWorkgroups}});

var<workgroup> smem: array<f32, {{smemSize}}>;

@compute @workgroup_size({{workgroupSize}})

fn main(@builtin(local_invocation_id) lid: vec3<u32>,

@builtin(global_invocation_id) gid: vec3<u32>,

@builtin(workgroup_id) wid: vec3<u32>) {

smem[lid.x] = a[gid.x];

workgroupBarrier();

for (var skip: u32 = 1; skip < wgs.x; skip = skip * 2) {

if (lid.x % skip == 0

&& lid.x + skip < wgs.x

&& gid.x + skip < arrayLength(&a)) {

smem[lid.x] = smem[lid.x] + smem[lid.x + skip];

}

workgroupBarrier();

}

if (lid.x == 0) {

out[wid.x] = smem[0];

}

}___________________________________

Test case 1

Workgroup Size ( 8, 1, 1 )

Total Workgroups ( 1, 1, 1 )

Shared Memory Size ( 8, 1, 1 )

Input a [ 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 ]

Expected [ 28 ]

___________________________________

Test case 2

Workgroup Size ( 8, 1, 1 )

Total Workgroups ( 2, 1, 1 )

Shared Memory Size ( 8, 1, 1 )

Input a [ 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 ]

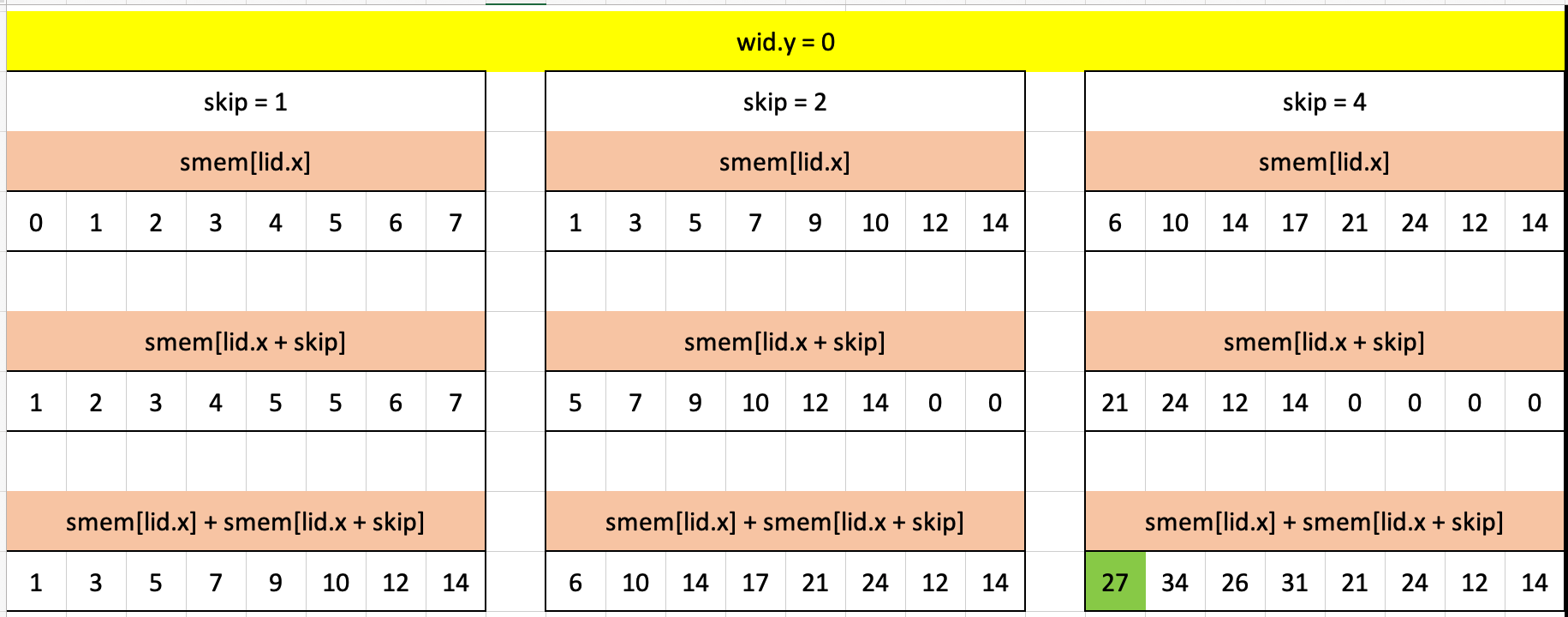

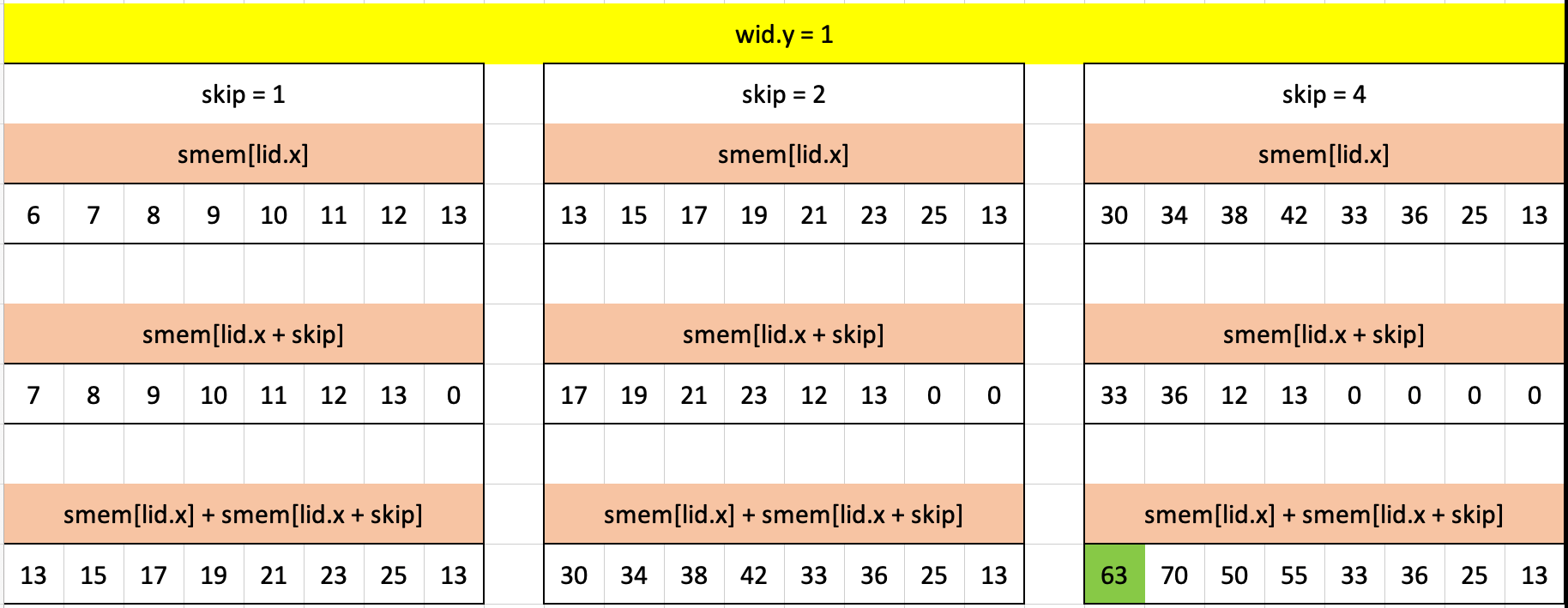

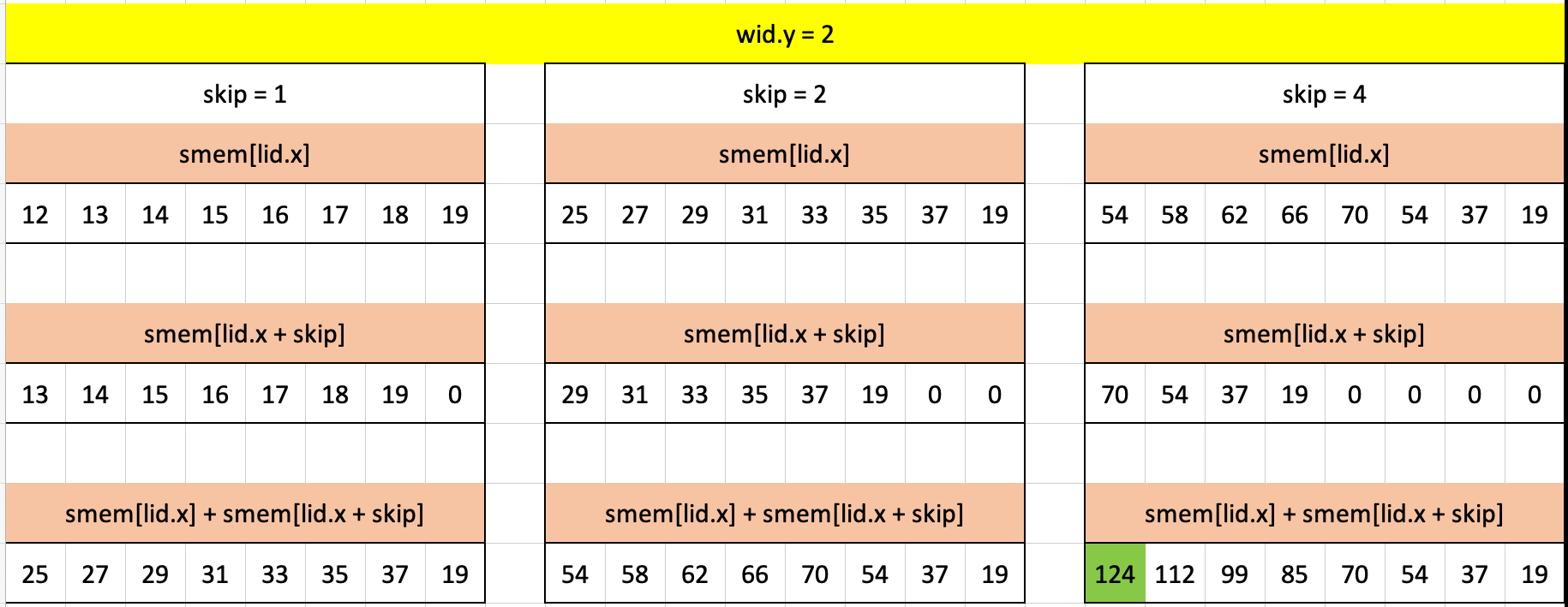

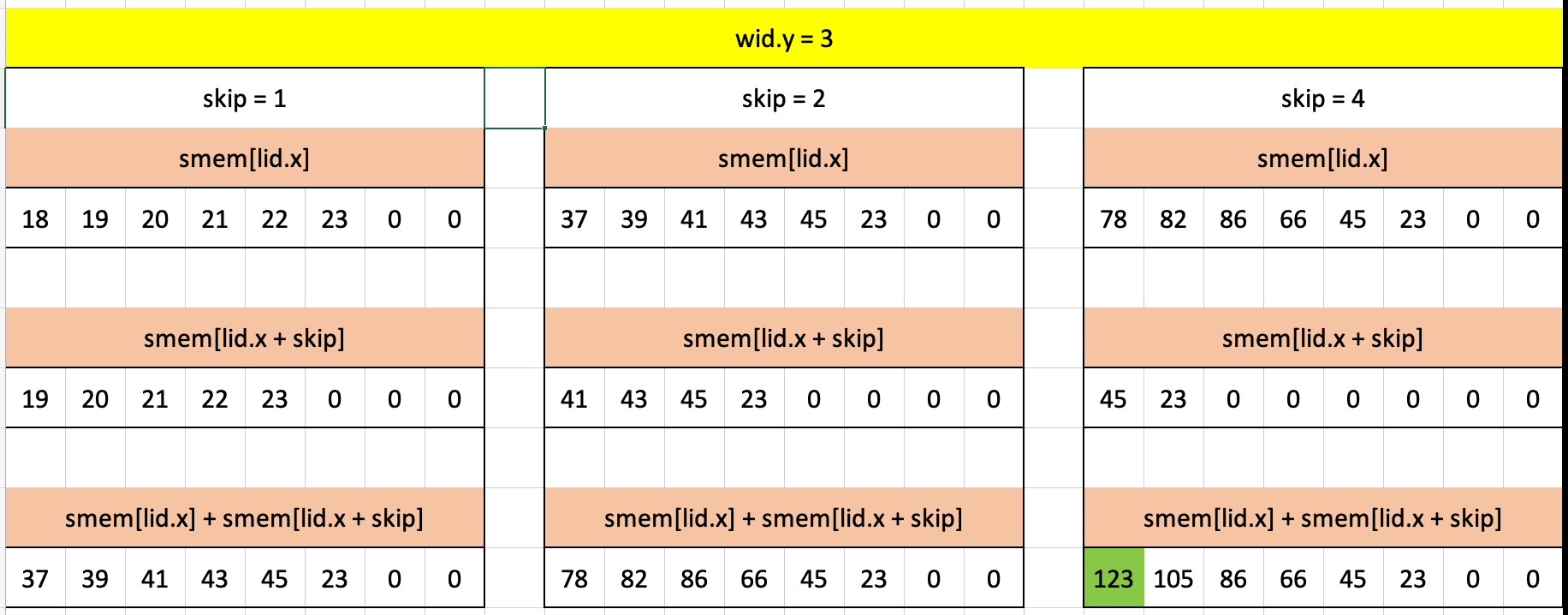

Expected [ 28 17 ]In this puzzle we want to take the block-wise cumulative sum. For Test case 1, there is only 1 block (workgroup) so we want the sum of the full array, which is 28. For Test case 2, we have two 8-thread blocks and a 10-element input array. The cumulative sum for the first block is the sum of the first 8 elements (28) and the cumulative sum for the second block is the sum of the next two elements (17).

The first line of the solution is simple: we want to load into shared memory the corresponding set of 8-elements from the input array:

smem[lid.x] = a[gid.x];Visualizing this in Excel for each workgroup:

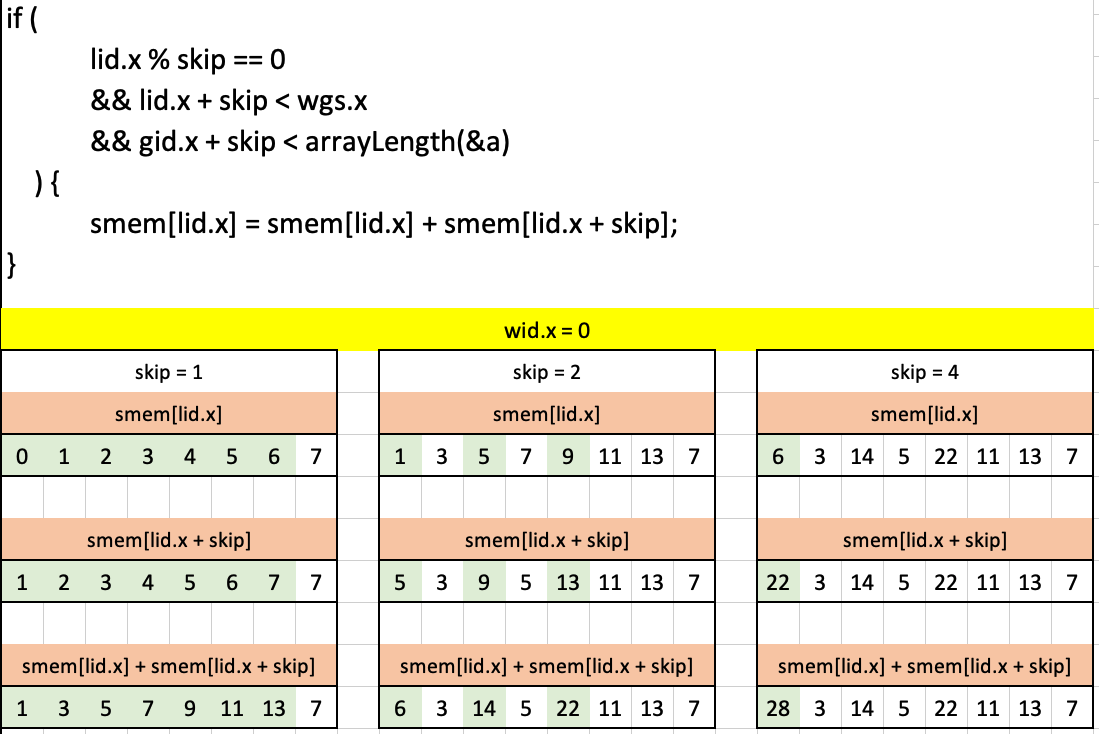

The next chunk of code is quite involved—its goal is to find the cumulative sum of the elements stored in shared memory following certain guards:

for (var skip: u32 = 1; skip < wgs.x; skip = skip * 2) {

if (lid.x % skip == 0

&& lid.x + skip < wgs.x

&& gid.x + skip < arrayLength(&a)) {

smem[lid.x] = smem[lid.x] + smem[lid.x + skip];

}

workgroupBarrier();

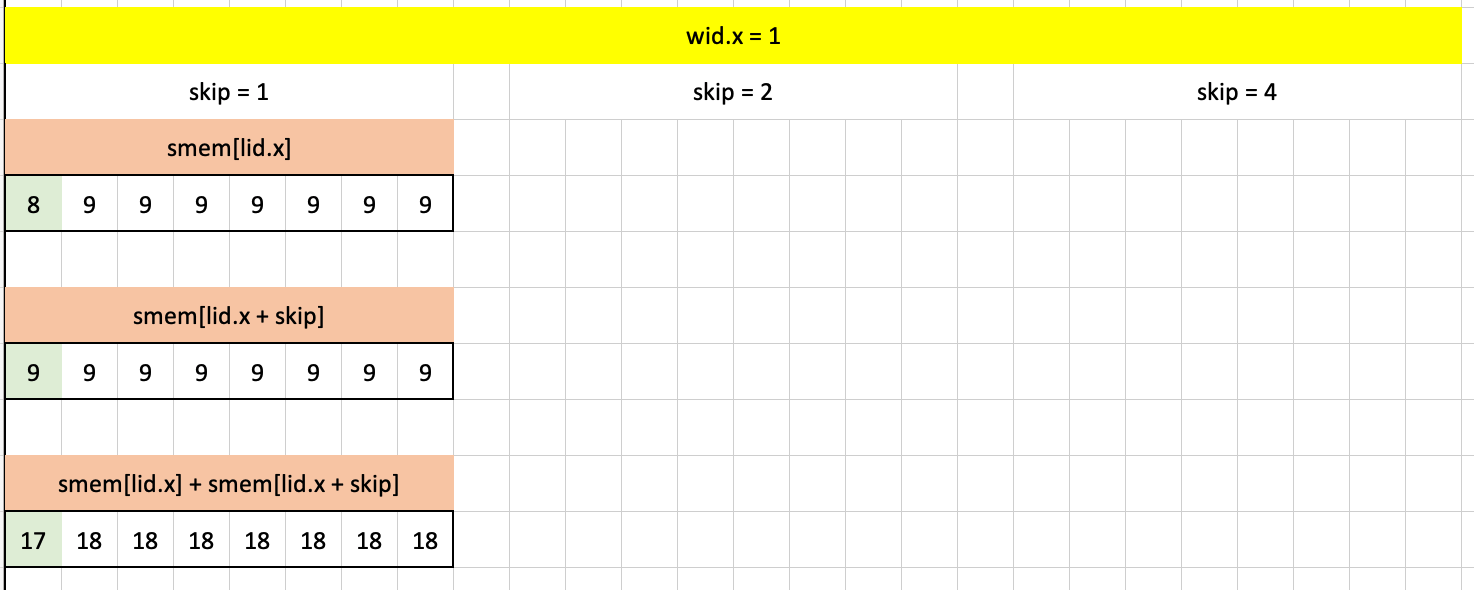

}Here’s what that code looks visualized in Excel where each column of arrays corresponds to each iteration of the loop. The cells highlighted in green in each array are the elements which pass the guard conditions in the if-statement:

For skip = 1, the first six elements pass the guard conditions. In each case (lid.x of 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5), lid.x % skip == 0 is true, lid.x + skip < wgs.x is true, and gid.x + skip < arrayLength(&a) is true. For the seventh element (lid.x = 7):

lid.x % skip == 0:7 % 1 == 0is truelid.x + skip < wgs.x:7 + 1 < 8is falsegid.x + skip < arrayLength(&a):7 + 1 < 8is false

For skip = 2: only the 0th, 2nd and 4th element pass the guard conditions. While the 6th element does pass the first guard (lid.x % skip == 0: 6 % 2 == 0 is true) it fails the second two guards as 6 + 2 is not less than wgs.x or arrayLength(&a).

Finally for skip = 4, only the 0th element passes all guard conditions. The 4th element does pass the first condition (lid.x % skip == 0: 4 % 4 == 0 is true) but fails the second two guards as 4 + 4 is not less than wgs.x or arrayLength(&a).

For each skip we slide the elements over by skip and sum them to the previous iteration’s smem.

In Test case 2, we have the same prefix sum (28) for the first block. We also have a second block for which the prefix sum is much simpler since the skip value in only one iteration of the for loop passes all guard conditions.

For skip = 1:

lid.x % skip == 0: is true for all 7 elements.lid.x + skip < wgs.x: is true for all 7 elements.gid.x + skip < arrayLength(&a):8 + 1 < 10is true only for the first element, so that’s the only sum that takes place (8 + 9 = 17).

For skip = 2 and skip = 4:

lid.x % skip == 0: is true for some elements.lid.x + skip < wgs.x: is true for some elements.gid.x + skip < arrayLength(&a): is true for no element, therefore the code inside the if-condition never runs.

Understanding the prefix sum algorithm took an unreasonable amount of time for me, and I’m still not completely comfortable, but the following visual did help solidify for me how it works. Green-highlighted cells are pairwise sums corresponding to the given skip. At the bottom I’ve listed out within which pairwise sums the given original array element is included.

Puzzle 13

@group(0) @binding(0) var<storage, read_write> a : array<f32>;

@group(0) @binding(1) var<storage, read_write> out : array<f32>;

const wgs = vec3({{workgroupSize}});

const twg = vec3({{totalWorkgroups}});

var<workgroup> smem: array<f32, {{smemSize}}>;

const nRows = 4;

@compute @workgroup_size({{workgroupSize}})

fn main(@builtin(local_invocation_id) lid: vec3<u32>,

@builtin(global_invocation_id) gid: vec3<u32>,

@builtin(workgroup_id) wid: vec3<u32>) {

let nCols = arrayLength(&a) / nRows;

smem[lid.x] = a[wid.y * nCols + lid.x];

workgroupBarrier();

for (var skip: u32 = 1; lid.x + skip < nCols; skip *= 2) {

smem[lid.x] += smem[lid.x+skip];

}

if (lid.x % nCols == 0) {

out[wid.y] = smem[0];

}

}___________________________________

Test case 1

Workgroup Size ( 8, 1, 1 )

Total Workgroups ( 1, 4, 1 )

Shared Memory Size ( 8, 1, 1 )

Input a

0 1 2 3 4 5

6 7 8 9 10 11

12 13 14 15 16 17

18 19 20 21 22 23

Expected [ 15 51 87 123 ]

___________________________________

Test case 2

Workgroup Size ( 8, 1, 1 )

Total Workgroups ( 1, 4, 1 )

Shared Memory Size ( 8, 1, 1 )

Input a

0 1 2 3

4 5 6 7

8 9 10 11

12 13 14 15

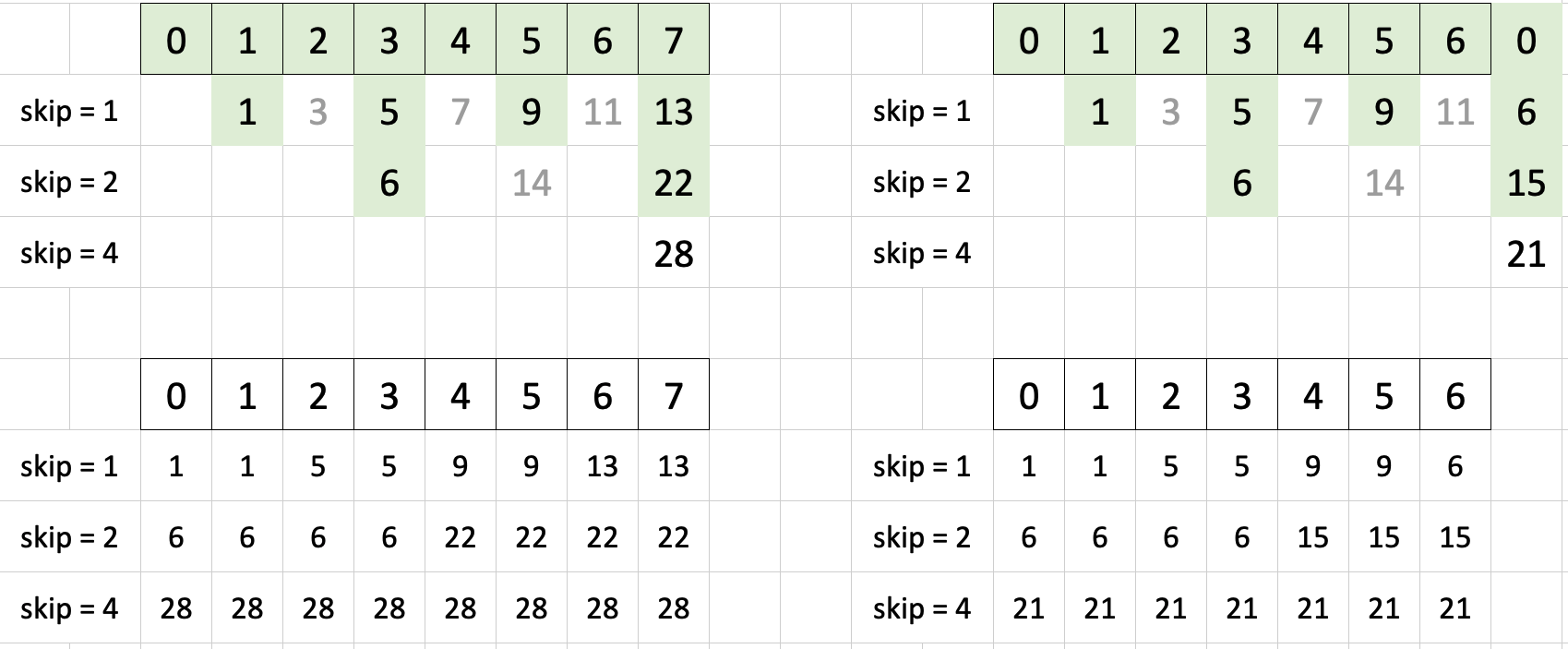

Expected [ 6 22 38 54 ]The goal of this exercise is to find the sum of each “row” in the input array. I put “row” in quotation marks because the input array is actually 1-D, so we look at the example to determine how many rows and columns we want.

I’ll walk through Test case 1.

The number of rows is a constant 4:

const nRows = 4;The number of columns is the length of the array divided by the number of rows:

let nCols = arrayLength(&a) / nRows;Each row of the input array is stored in a separate workgroup’s shared memory. This is achieved by multiplying nCols by wid.y before adding lid.x:

smem[lid.x] = a[wid.y * nCols + lid.x];Here’s what that index, wid.y * nCols + lid.x, looks like for each row:

wid.y |

wid.y * nCols + lid.x |

|---|---|

0 |

0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 |

1 |

6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 |

2 |

12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17 |

3 |

18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23 |

Visualizing how, using the index wid.y * nCols + lid.x, we load the input array a into each workgroup’s shared memory smem:

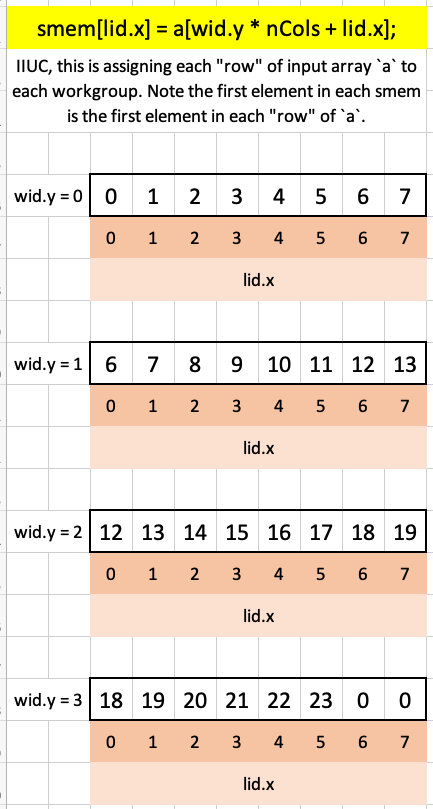

Next, similar to the previous puzzle’s prefix sum algorithm, we iterate through each row, accumulating the sum by iterating over array elements in increasing skip amounts:

for (var skip: u32 = 1; lid.x + skip < nCols; skip *= 2) {

smem[lid.x] += smem[lid.x+skip];

}Visualizing that for-loop in the first workgroup, in which we find the sum of the first row of a (highlighted in green):

I’m not 100% sure why we don’t have guards in this puzzle as we did in Puzzle 12, but my guess is that we don’t need it here since the number of threads in the workgroup (8) is the same as the shared memory size (8).

Visualizing the for-loops that occur in the other three workgroups, one for each row of the input array with the final cumulative sum highlighted in green:

Puzzle 14

@group(0) @binding(0) var<storage, read_write> a: array<f32>;

@group(0) @binding(1) var<storage, read_write> b: array<f32>;

@group(0) @binding(2) var<storage, read_write> output: array<f32>;

const wgs = vec3({{workgroupSize}});

const twg = vec3({{totalWorkgroups}});

const tileSize = vec3({{workgroupSize}});

var<workgroup> a_shared: array<f32, 256>;

var<workgroup> b_shared: array<f32, 256>;

@compute @workgroup_size({{workgroupSize}})

fn main(

@builtin(local_invocation_id) lid: vec3<u32>,

@builtin(global_invocation_id) gid: vec3<u32>,

@builtin(workgroup_id) wid: vec3<u32>) {

let N = u32(sqrt(f32(arrayLength(&a))));

let i = wid.x * wgs.x + lid.x;

let j = wid.y * wgs.y + lid.y;

let local_i = lid.x;

let local_j = lid.y;

var acc: f32 = 0.0;

for (var k: u32 = 0u; k < N; k = k + tileSize.x) {

if (j < N && k + local_i < N) {

a_shared[local_j * tileSize.x + local_i]

= a[j * N + (k + local_i)];

} else {

a_shared[local_j * tileSize.x + local_i] = 0.0;

}

if (i < N && k + local_j < N) {

b_shared[local_j * tileSize.x + local_i]

= b[i + (k + local_j) * N];

} else {

b_shared[local_j * tileSize.x + local_i] = 0.0;

}

workgroupBarrier();

let local_k_max = min(tileSize.x, N - k);

for (var local_k: u32 = 0u;

local_k < local_k_max;

local_k = local_k + 1u) {

acc += a_shared[local_j * tileSize.x + local_k]

* b_shared[local_k * tileSize.x + local_i];

}

workgroupBarrier();

}

if (i < N && j < N) {

output[i + j * N] = acc;

}

}___________________________________

Test case 1

Workgroup Size ( 3, 3, 1 )

Total Workgroups ( 1, 1, 1 )

Shared Memory Size ( 3, 3, 1 )

Input a

0 1

2 3

Input b

0 1

2 3

Expected

2 3

6 11

___________________________________

Test case 2

Workgroup Size ( 1, 1, 1 )

Total Workgroups ( 2, 2, 1 )

Shared Memory Size ( 3, 3, 1 )

Input a

0 1

2 3

Input b

0 1

2 3

Expected

2 3

6 11

___________________________________

Test case 3

Workgroup Size ( 4, 4, 1 )

Total Workgroups ( 1, 1, 1 )

Shared Memory Size ( 4, 4, 1 )

Input a

0 1 2

3 4 5

6 7 8

Input b

9 10 11

12 13 14

15 16 17

Expected

42 45 48

150 162 174

258 279 300

___________________________________

Test case 4

Workgroup Size ( 2, 2, 1 )

Total Workgroups ( 2, 2, 1 )

Shared Memory Size ( 2, 2, 1 )

Input a

0 1 2

3 4 5

6 7 8

Input b

9 10 11

12 13 14

15 16 17

Expected

42 45 48

150 162 174

258 279 300

___________________________________

Test case 5

Workgroup Size ( 2, 2, 1 )

Total Workgroups ( 2, 2, 1 )

Shared Memory Size ( 2, 2, 1 )

Input a

0 1 2 3

4 5 6 7

8 9 10 11

12 13 14 15

Input b

0 1 2 3

4 5 6 7

8 9 10 11

12 13 14 15

Expected

56 62 68 74

152 174 196 218

248 286 324 362

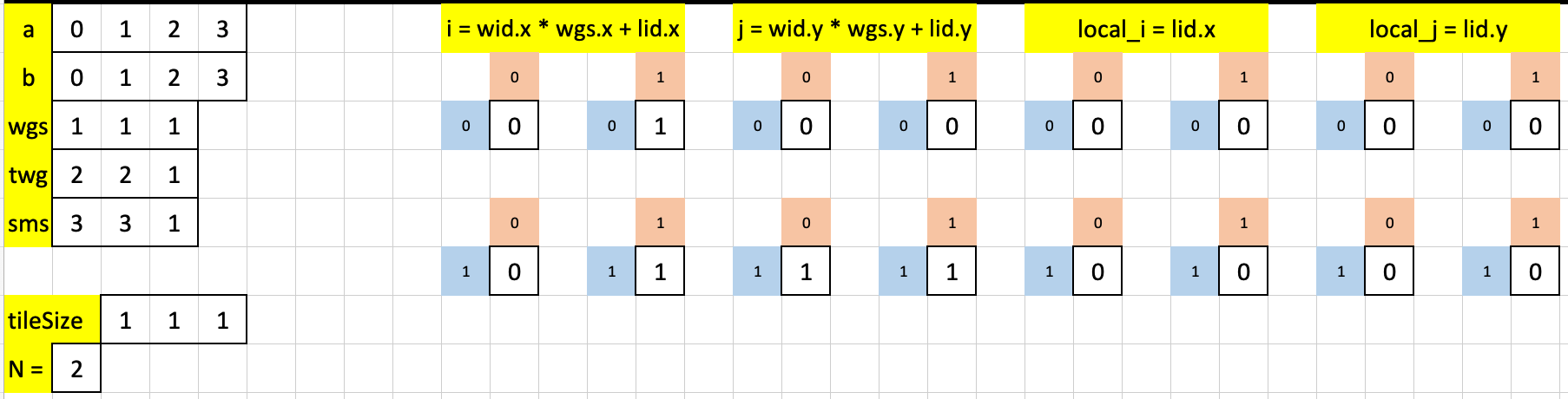

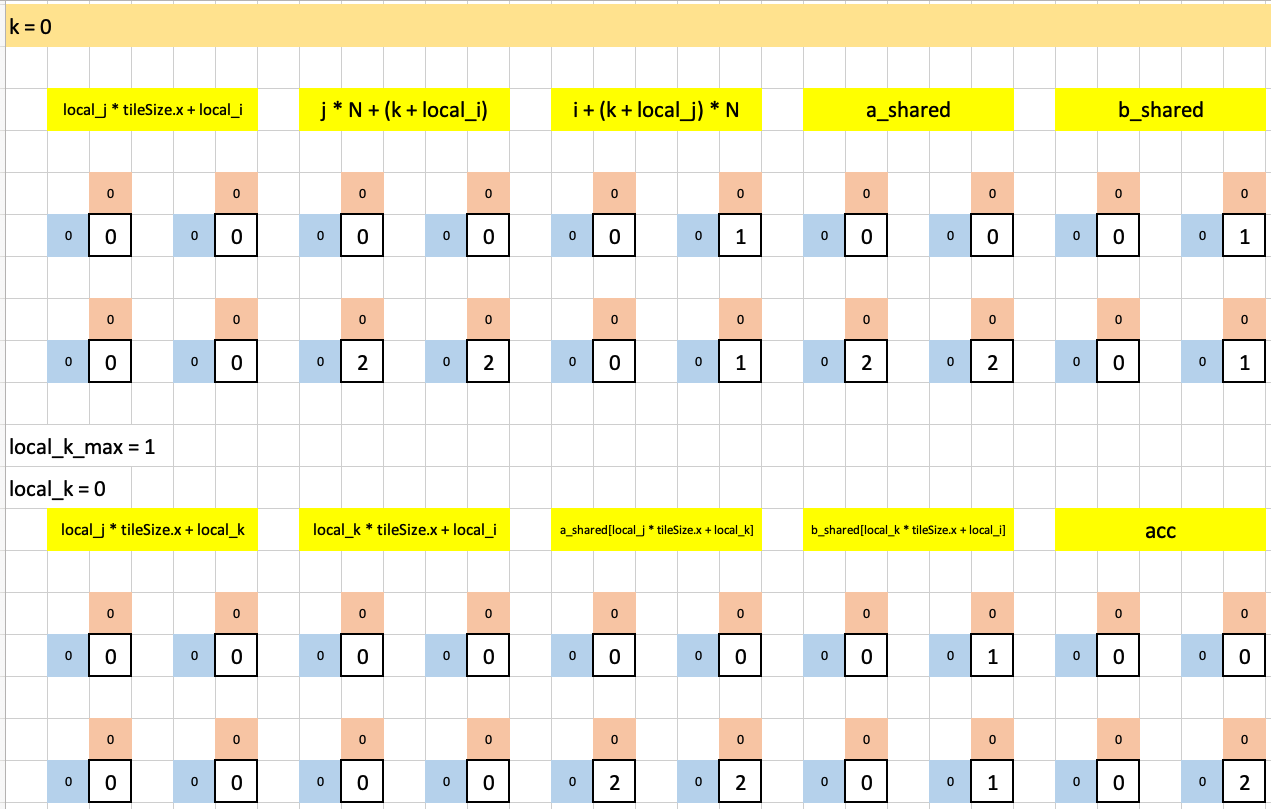

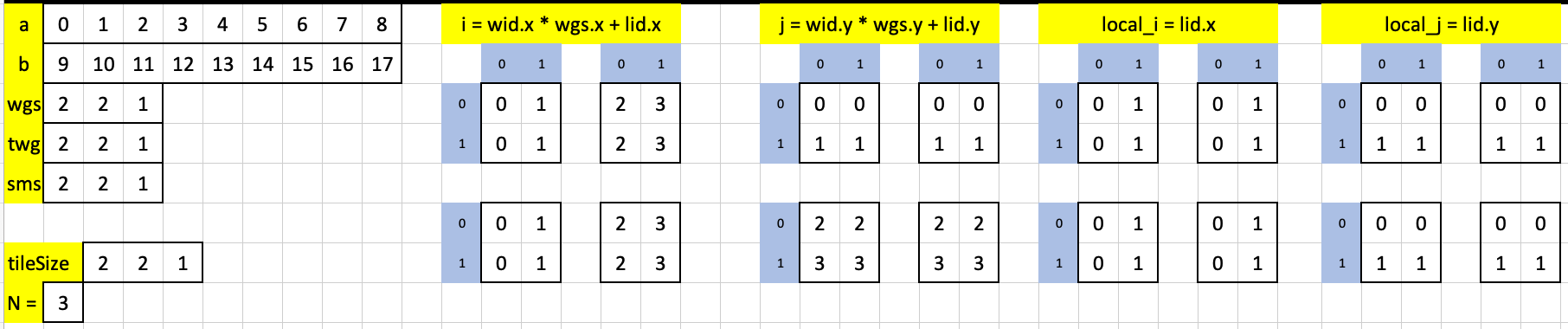

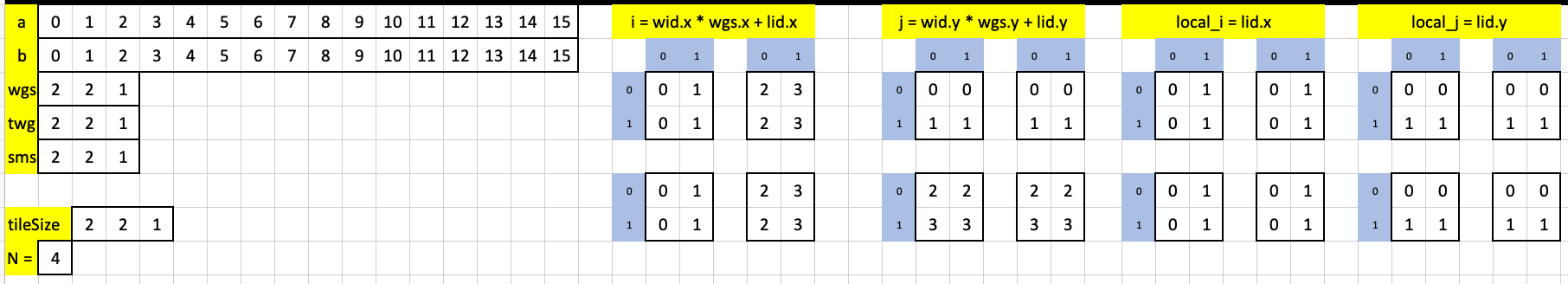

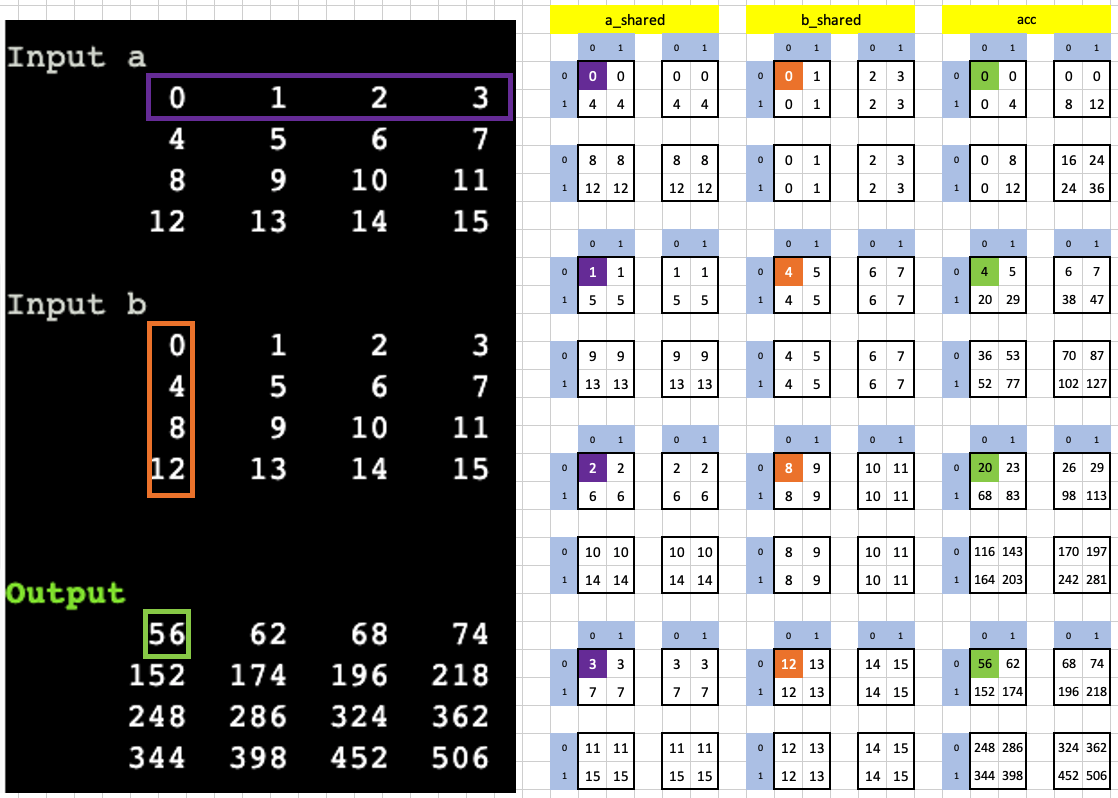

344 398 452 506Walking through this puzzle’s official solution was another pivotal point in my understanding of GPU parallelism. I’ll start with Test case 1.

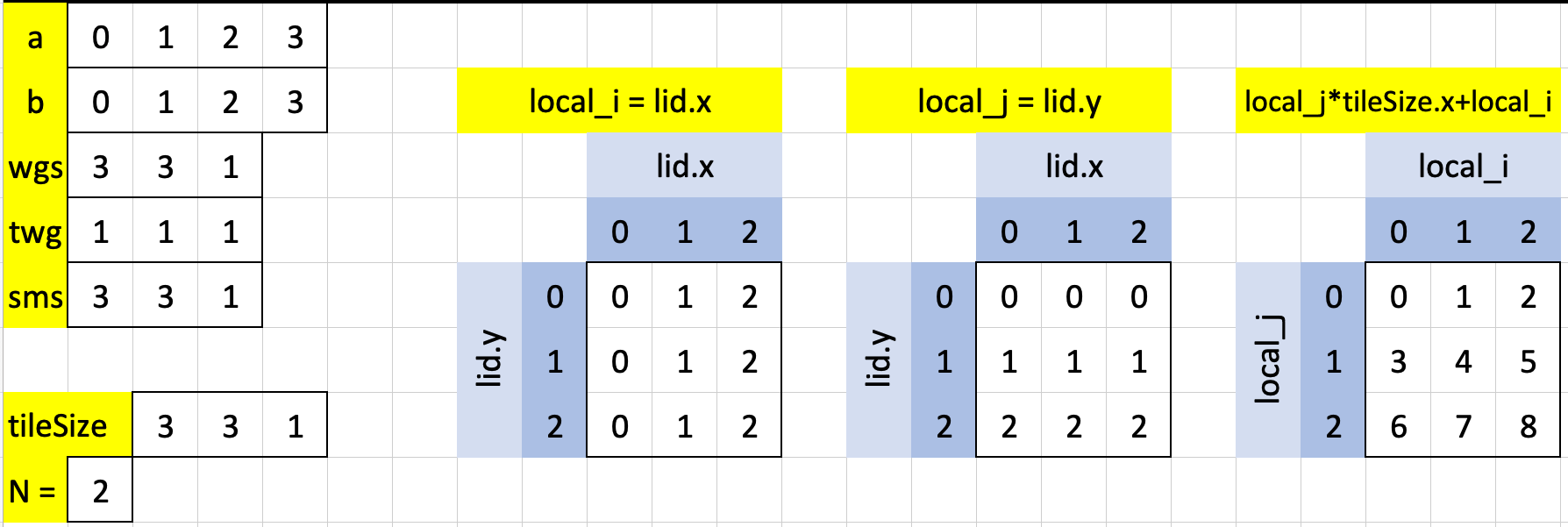

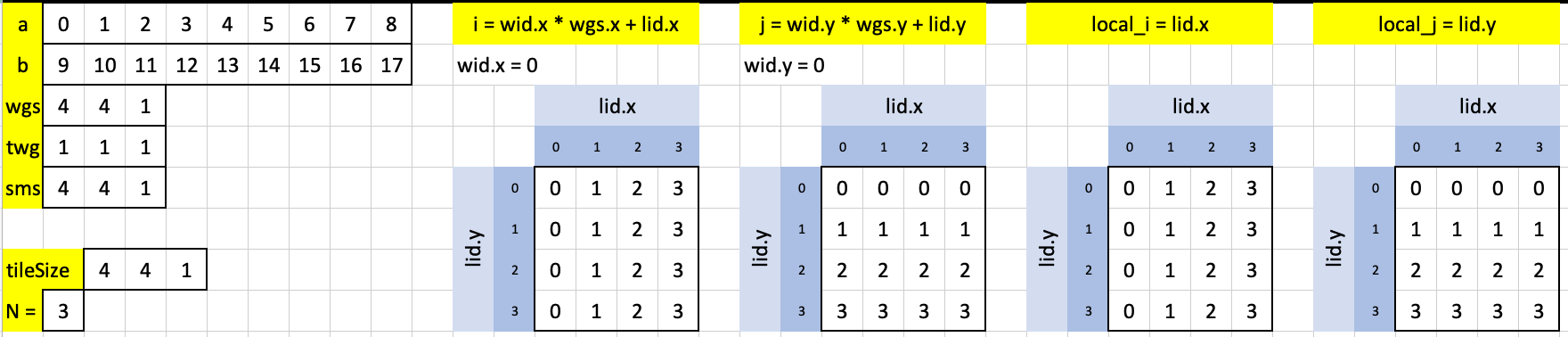

There are three, what I call, “core indexes” that this solution establishes: local_i, local_j and local_j * tileSize.x + local_i. We can see that local_i indexes across rows while local_j indexes down columns. local_j * tileSize.x + local_i indexes the threads left-to-right and top-to-bottom.

let N = u32(sqrt(f32(arrayLength(&a))));

let i = wid.x * wgs.x + lid.x;

let j = wid.y * wgs.y + lid.y;

let local_i = lid.x;

let local_j = lid.y;The indexes i and j (which we’ll look at shortly), because we have only 1 workgroup for Test case 1, are the same as local_i and local_j, respectively.

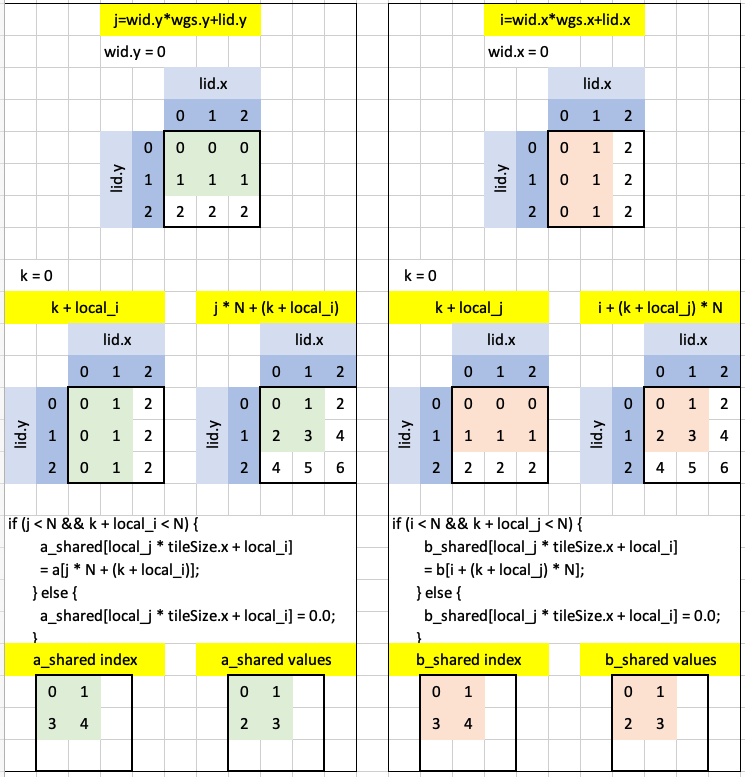

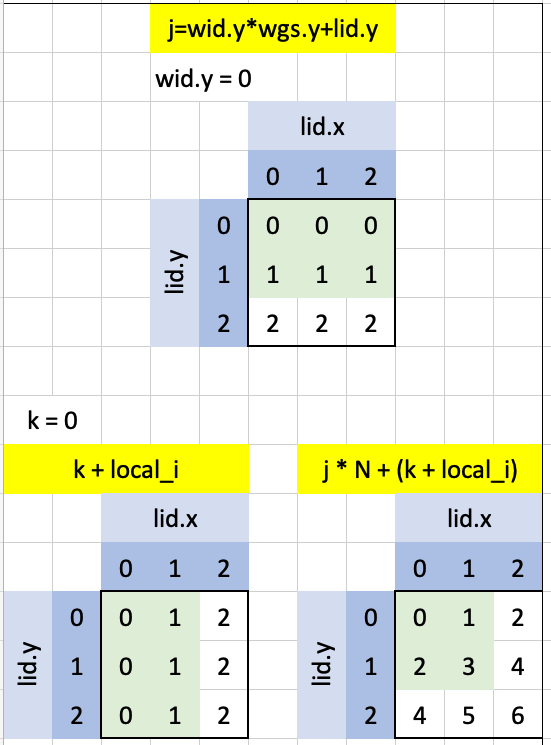

Let’s next tackle the code which loads input arrays a and b into shared memory a_shared and b_shared, respectively:

if (j < N && k + local_i < N) {

a_shared[local_j * tileSize.x + local_i] = a[j * N + (k + local_i)];

} else {

a_shared[local_j * tileSize.x + local_i] = 0.0;

}

if (i < N && k + local_j < N) {

b_shared[local_j * tileSize.x + local_i] = b[i + (k + local_j) * N];

} else {

b_shared[local_j * tileSize.x + local_i] = 0.0;

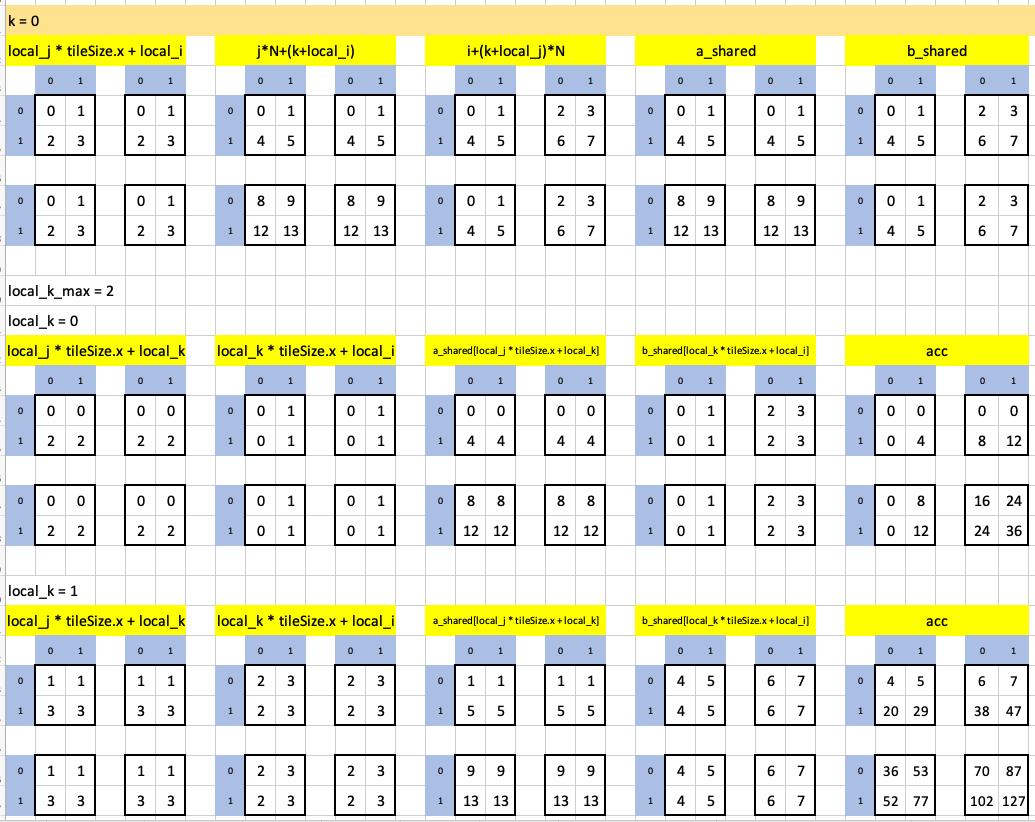

}Note that this code runs inside a for-loop:

for (var k: u32 = 0u; k < N; k = k + tileSize.x) { ... }but since N is 2 and tileSize.x is 3 for this test case this outermost loop runs only once.

The visualization below is, at the highest level, broken into two boxes: one for a_shared (left) and one for b_shared (right).

if (j < N && k + local_i < N) {

a_shared[local_j * tileSize.x + local_i] = a[j * N + (k + local_i)];

} else {

a_shared[local_j * tileSize.x + local_i] = 0.0;

}Let’s walk through a_shared first.

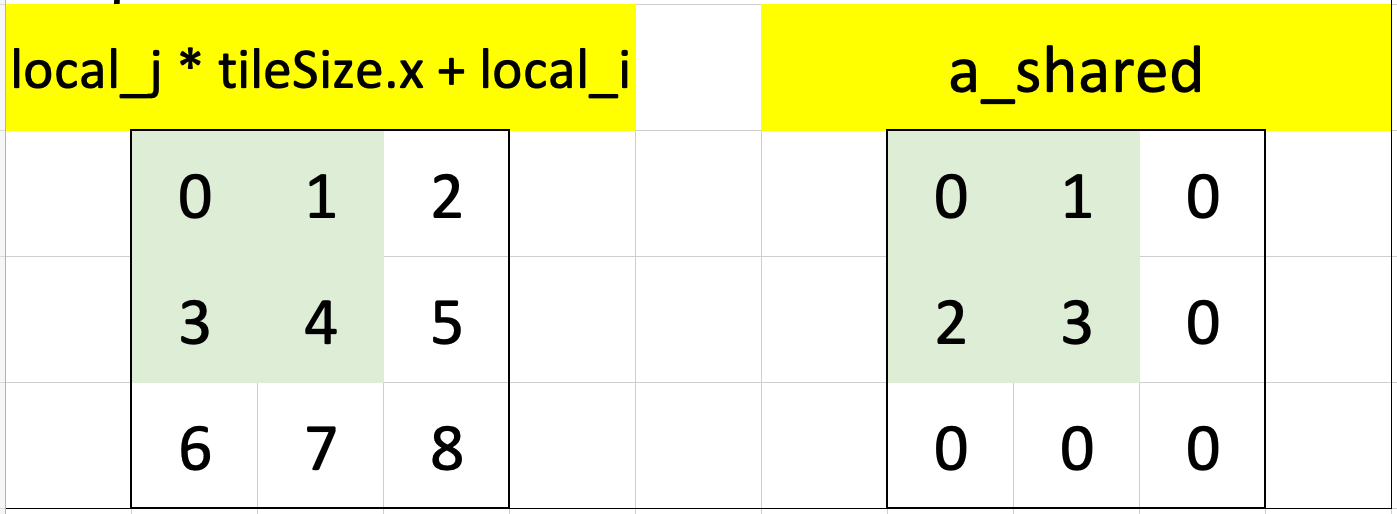

The cells highlighted in green are the threads that satisfy the guard condition j < N. In this single iteration of the outermost loop, k = 0. The second condition in the guard is k + local_i < N, the threads in the workgroup which satisfy this condition are highlighted in green. When combining the use of indexes j and k + local_i we see that the threads which satisfy the full condition j < N && k + local_i < N are highlighted in green. There are four such threads and they are indexed 0, 1, 2, 3—these are used to index into a when assigning values to a_shared:

The grid on the right shows the values of a that are assigned to a_shared at the indexes in the grid shown on the left:

Here’s a mapping of index to value for a_shared—this is key in understanding the next part of the code:

| Index | Value |

|---|---|

| 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 1 |

| 3 | 2 |

| 4 | 3 |

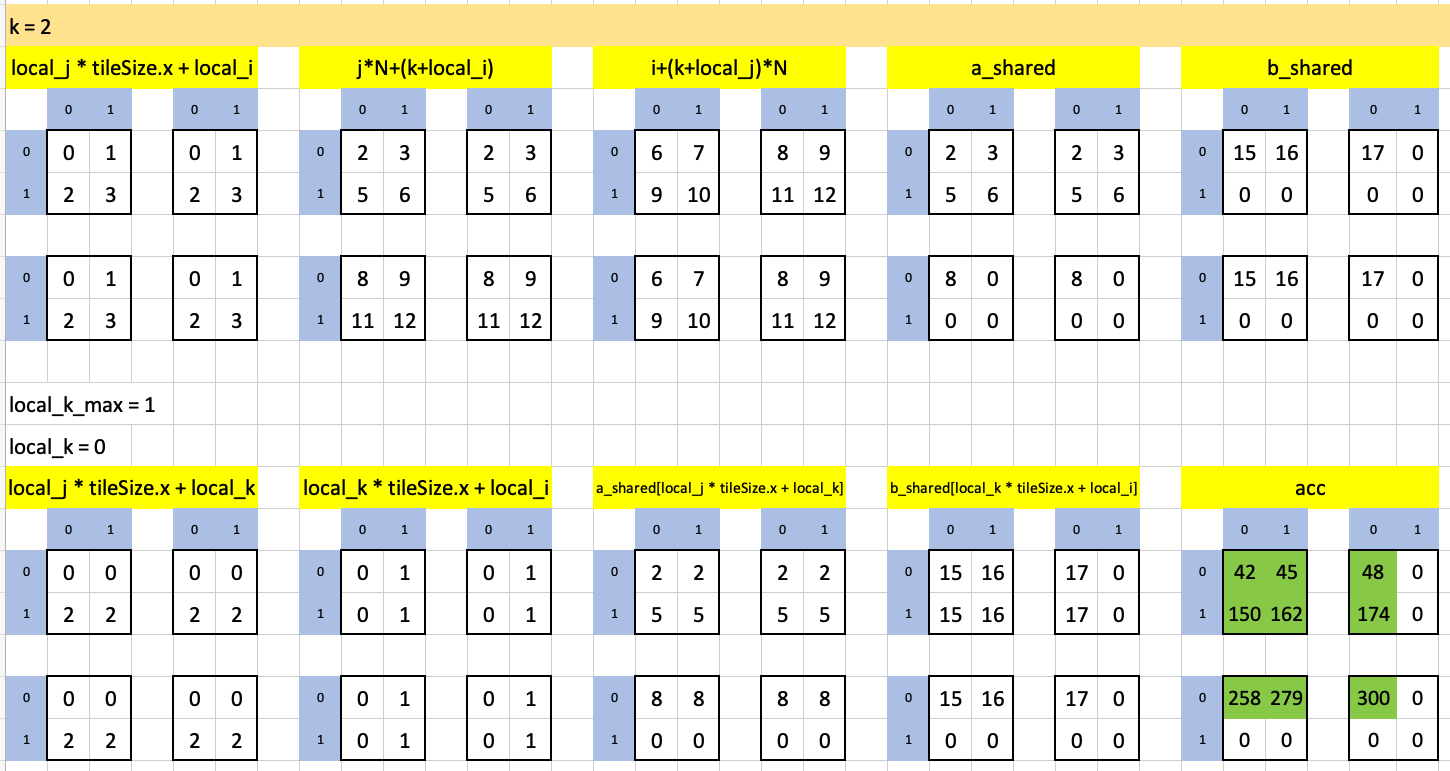

We can now go into the inner-most loop:

let local_k_max = min(tileSize.x, N - k);

for (

var local_k: u32 = 0u;

local_k < local_k_max;

local_k = local_k + 1u

) {

acc += a_shared[local_j * tileSize.x + local_k] * b_shared[local_k * tileSize.x + local_i];

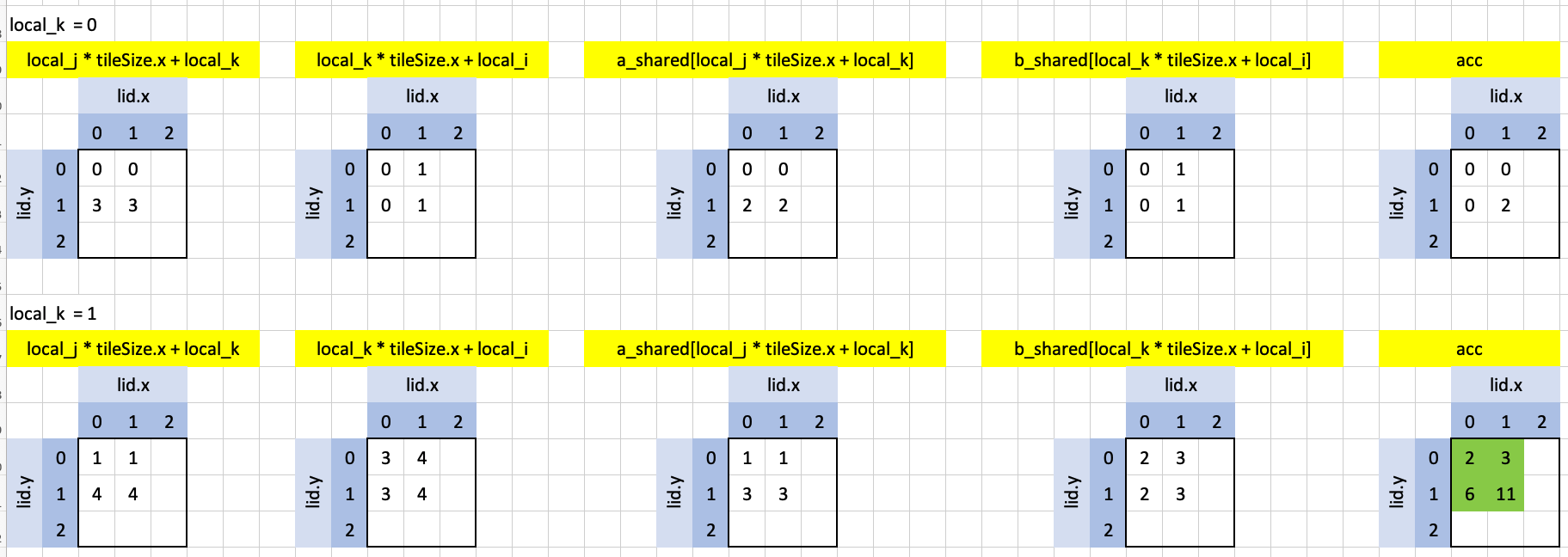

}local_k_max is 2 (N - k), so the loop iterates twice, as shown in the visualization below:

Going left-to-right in each loop iterations:

local_j * tileSize.x + local_k: the index intoa_shared.local_k * tileSize.x + local_i: the index intob_shared.a_shared[local_j * tileSize.x + local_k]: the values ofa_sharedused in the loop iteration.b_shared[local_k * tileSize.x + local_i]: the values ofb_sharedused in the loop iteration.acc: the element-wise product ofa_shared[local_j * tileSize.x + local_k]andb_shared[local_k * tileSize.x + local_i].

Note that while acc looks like an array, it’s actually just a single floating point value (var acc: f32 = 0.0;) which has a different value in each workgroup thread. That is the power of indexing!

Looking at the matrix multiplication between a and b as we would do it by hand:

\[\left[\begin{matrix}0 & 1 \ 2 & 3\end{matrix}\right] \times \left[\begin{matrix}0 & 1 \ 2 & 3\end{matrix}\right] = \left[\begin{matrix}2 & 3 \ 6 & 11\end{matrix}\right]\]

The top-left value in the result (2) is the dot product between the first row of a and the first column of b. In our GPU-implementation, that dot product occurs across two loop iterations and different threads as shown in the purple-highlighted cells below:

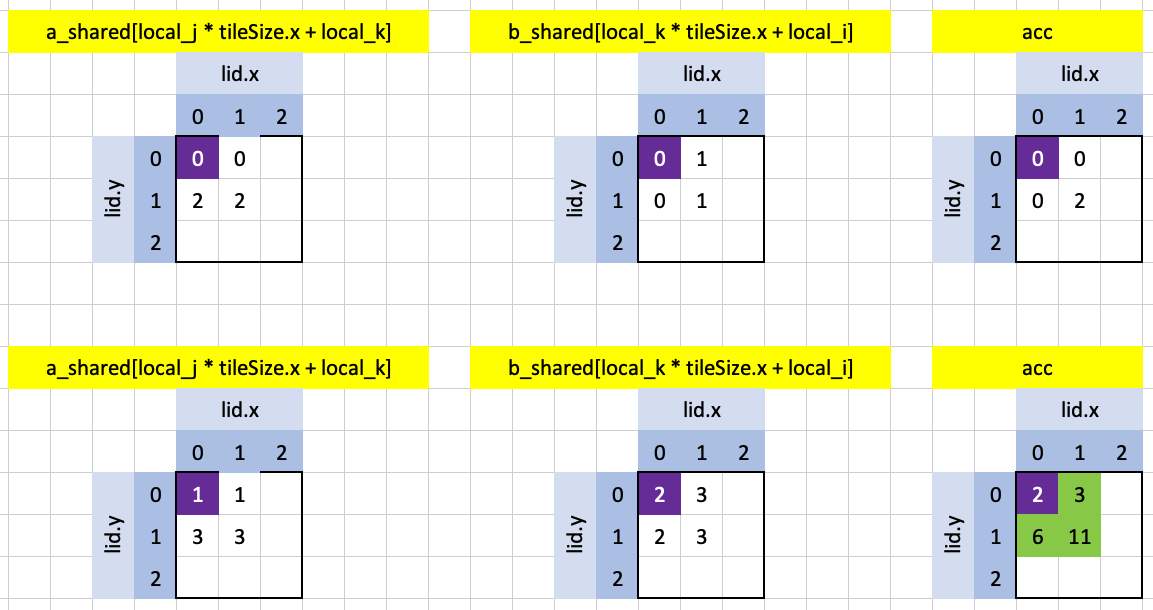

Let’s now take a look at test case 2.

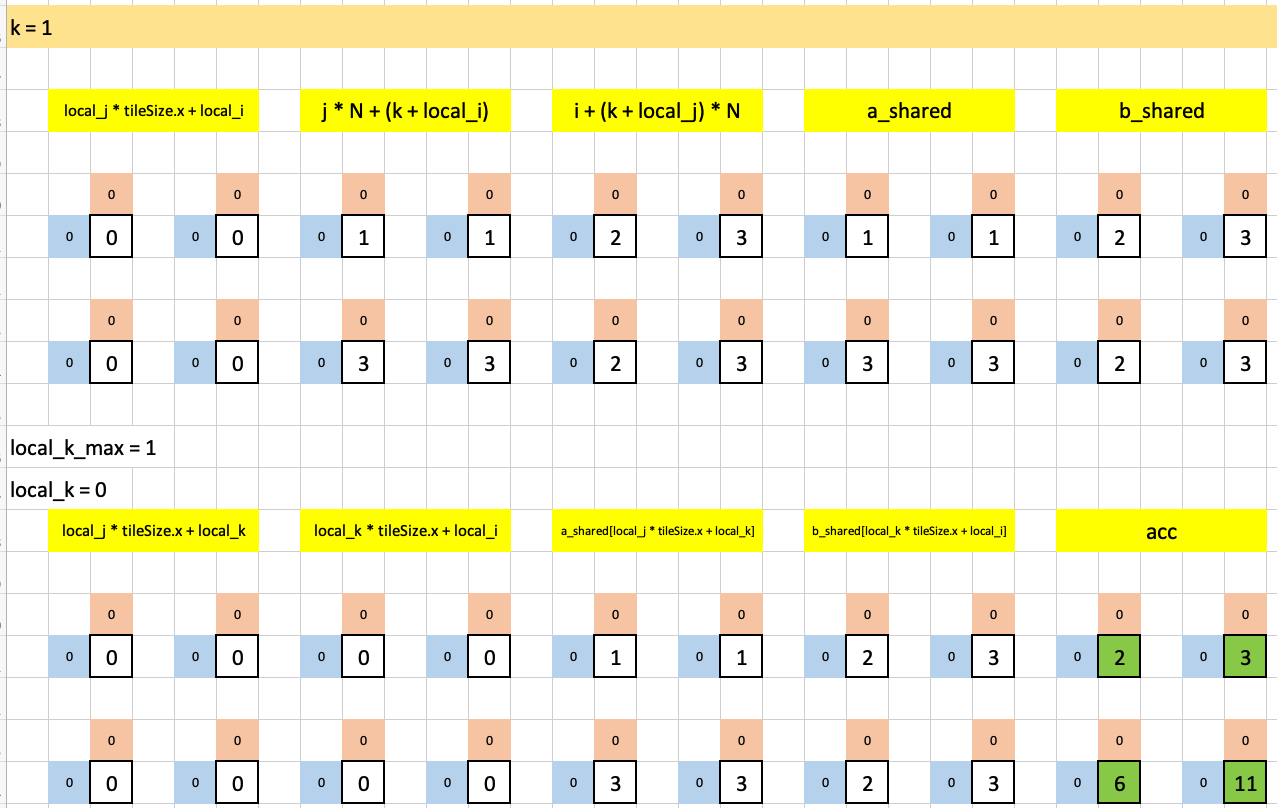

Here are the constants and “core indexes” for this test case (same code, different organization than test case 1).

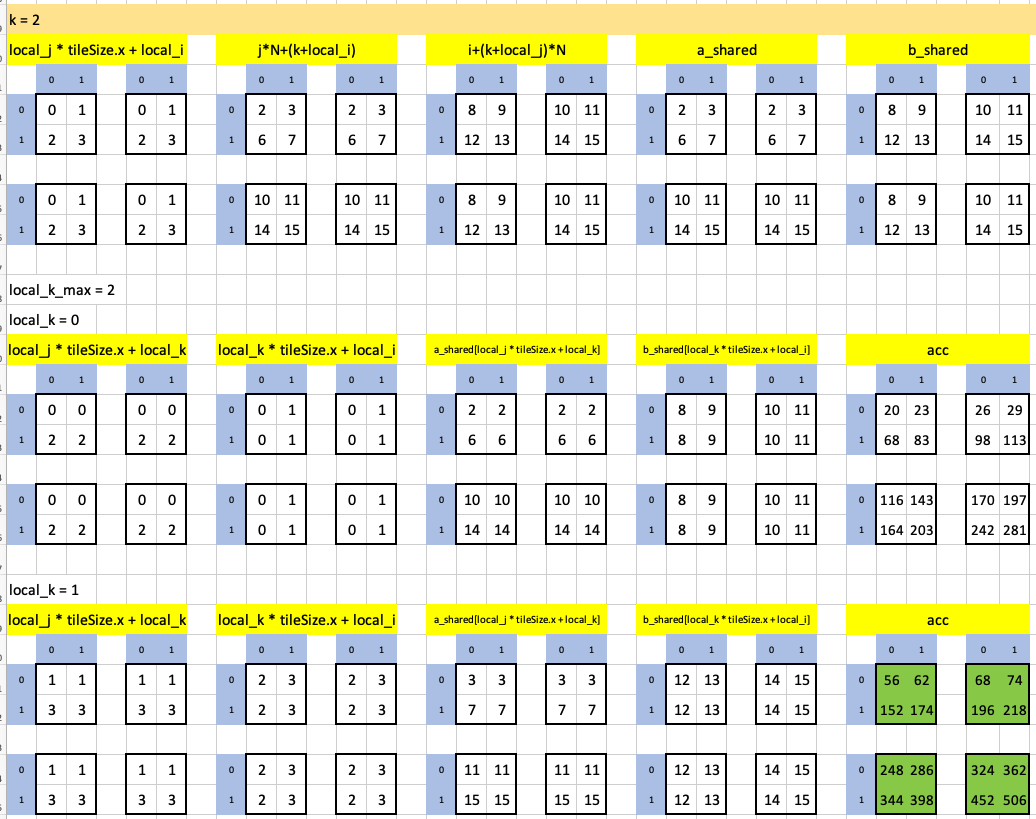

For this test case, the outermost loop runs twice and each time the innermost loop runs once. Here’s the first iteration of the outermost loop:

and here’s the second iteration of the outermost loop (with its single iteration of the innermost loop):

Note that the value of acc at the end of each outermost loop iteration is the same as test case 1 except that now, since we have 4 workgroups each with 1 thread, each value of the four values of acc in test case 2 are assigned to one workgroup each.

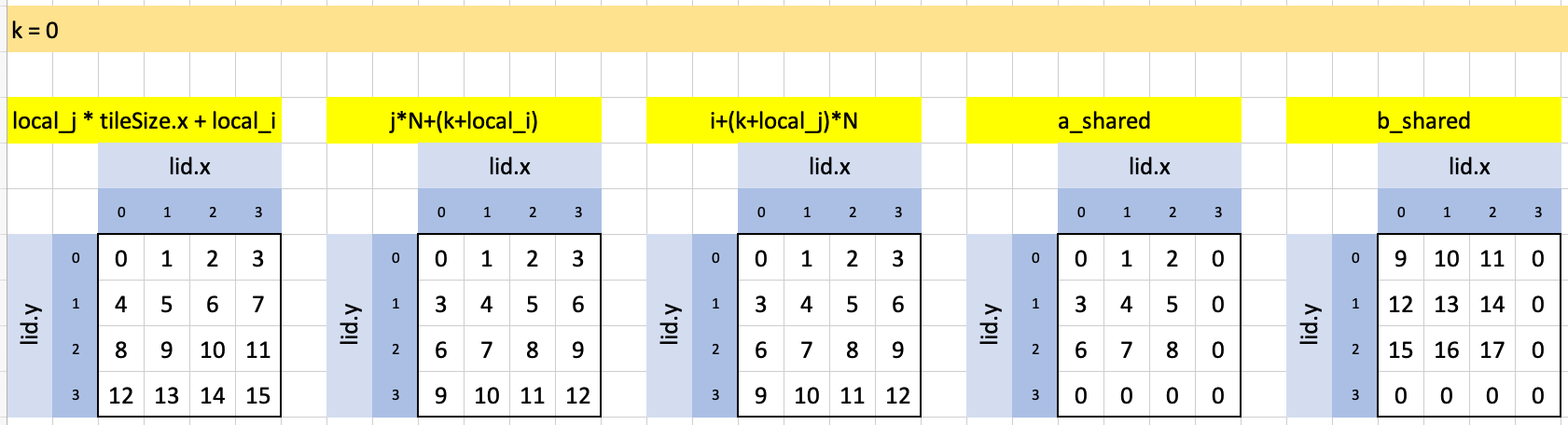

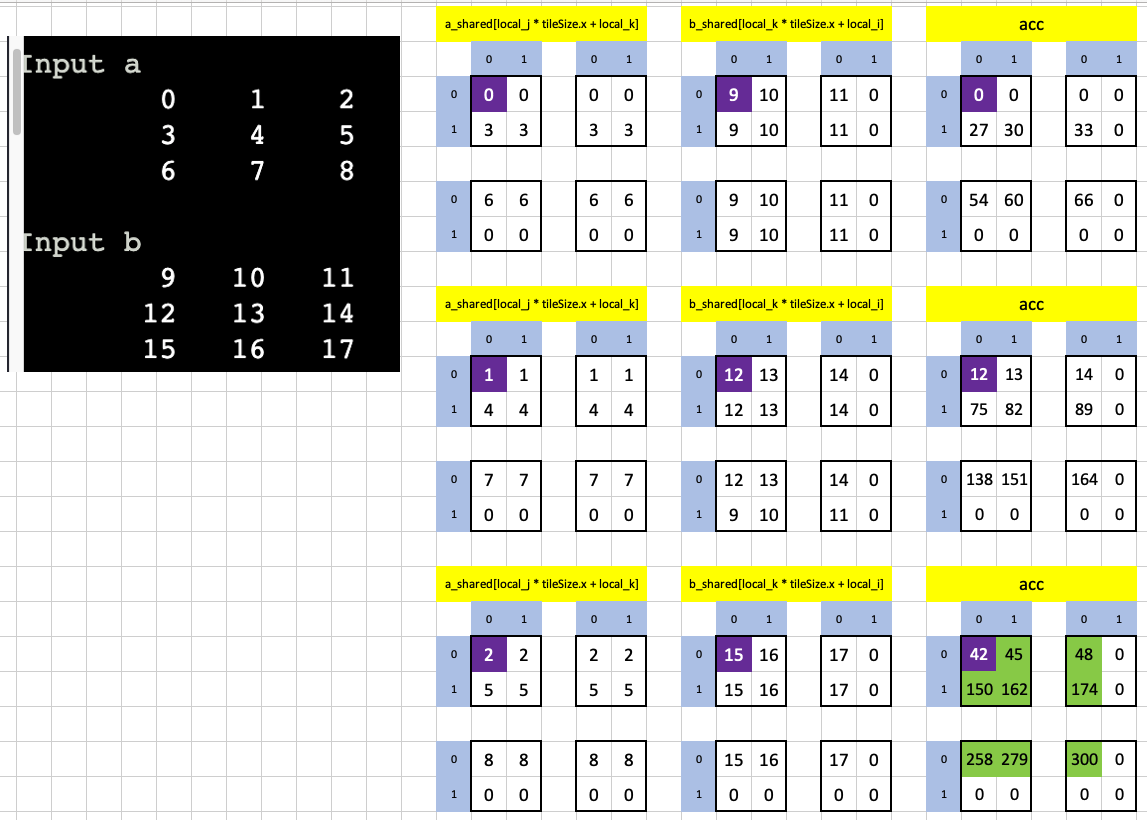

Let’s move on to test case 3, in which we now are performing matrix multiplication between two 3x3 matrices in a single workgroup, analogous to test case 1.

The constants and core indexes:

The outermost loop, for this test case, runs only once. Here are the indexes used and values of a_shared and b_shared:

local_k_max is 3 so the innermost loop runs three times, with the final result highlighted in green:

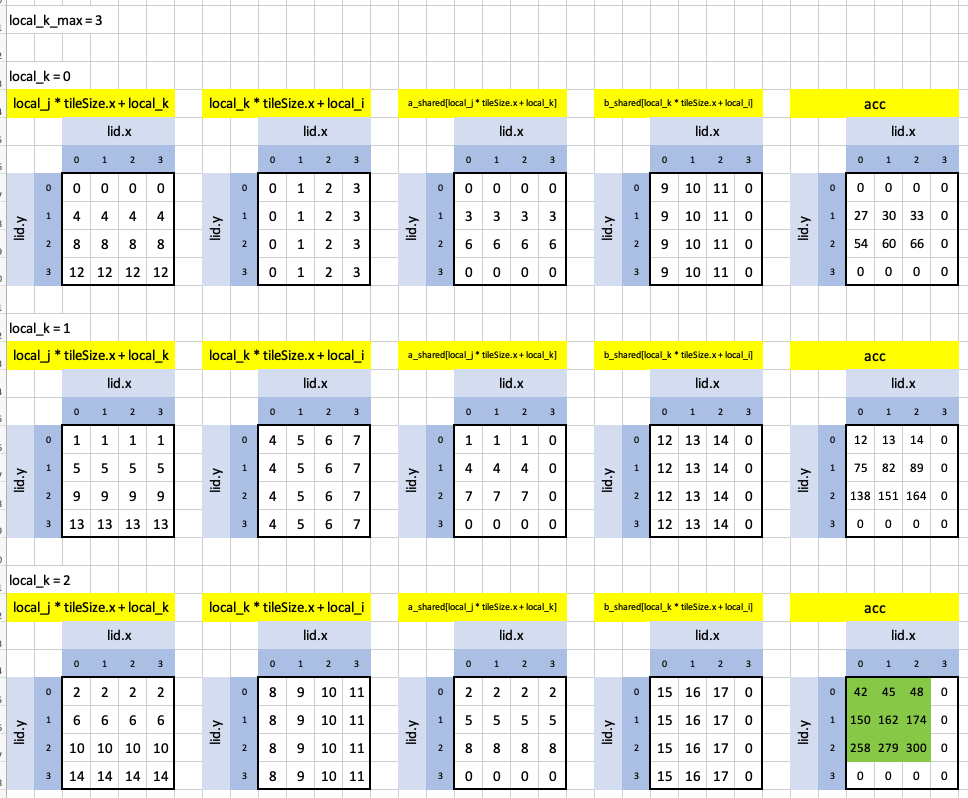

Moving on to test case 4, which is unique so far in the sense that the number of threads per workgroup (2x2 = 4) is less than the number of elements in each matrix being multiplied (3x3 = 9). However, the core indexes and inner- and outermost loops still suffice.

The constants and core indexes:

The outermost loop has two iterations. Here is the first iteration, in which the innermost loop runs twice:

In the second-most iteration of the outermost loop, the innermost loop runs only once, note the final result highlighted in green:

Here’s a visualization of how the dot product of the first row of a (0, 1, 2) and the first column of b (9, 12, 15) accumulates through element-wise products across different loop iterations to yield the final result of 42:

The last test case is test case 5, in which the number of available threads (16) matches the number of elements in each input array (16).

The constants and core indexes:

The outermost loop runs twice and each time the innermost loop runs twice as well. Here’s the first iteration of the outermost loop:

Here is the second iteration of the outermost loop (the inner loop runs twice). Note the final result highlighted in green, uses up all threads:

Here I visualize the dot product between the first row of a (0, 1, 2, 3) and the first column of b (0, 4, 8, 12) to yield the result 56.

That’s a wrap for the official solutions’ walk through! You can find the Excel spreadsheet here.